|

Colonisation of Africa |

Colonisation of Africa |

Colonisation of Africa | Colonisation of Africa |

Before you travel to Africa as a volunteer, explore the rich and varied history of the continent.

More >

|

The social and cultural impact of colonisation was equally devastating and far-reaching. Artificial borders, drawn by European diplomats in Berlin with little regard for pre-existing ethnic, linguistic, or cultural realities, fractured cohesive communities and lumped disparate groups together, sowing seeds for future conflicts. Traditional political structures, often complex and nuanced, were either co-opted or destroyed, leading to a loss of indigenous governance systems. Education, where it was provided, was typically rudimentary, designed to train clerks and subservient labourers, and heavily biased towards European languages, histories, and values, often at the expense of indigenous knowledge systems. Christian missionaries, often preceding or accompanying colonial forces, actively campaigned to convert African populations, challenging traditional belief systems and sometimes acting as extensions of colonial power. Pervasive racism and segregation became institutionalised, with Africans relegated to second-class citizenship in their own lands. The "civilising mission" was often a thin veil for racial superiority and subjugation, creating deep psychological scars that would last for generations.

The two World Wars significantly weakened European colonial powers further, while simultaneously boosting nationalist sentiments among educated African elites who had fought alongside their colonial masters. The post-WWII era saw a rapid wave of decolonisation, with most African nations gaining independence in the 1950s and 1960s. The legacy of colonisation continues to shape Africa today. Economically, many African nations inherited economies heavily reliant on the export of a few raw materials, making them vulnerable to global market fluctuations. Industrialisation was stifled, leading to persistent underdevelopment and dependence. Politically, the arbitrary colonial borders and the "divide and rule" tactics often exacerbated ethnic tensions, contributing to post-independence political instability, civil wars, and the rise of authoritarian regimes. Weak institutions, designed for colonial control rather than national development, became a recurring challenge. Socially, the lingering effects of racial hierarchies, trauma, and the disruption of traditional social fabrics are still felt. Culturally, while European languages became official languages in many countries, there was also a loss or marginalisation of indigenous languages and traditions. While some infrastructure was built, it was often designed for extraction rather than integrated development, leaving many regions underserved. The psychological impact, including identity crises and inferiority complexes, has been profound, though these have been countered by immense resilience, cultural revival, and a strong sense of pan-African identity. |

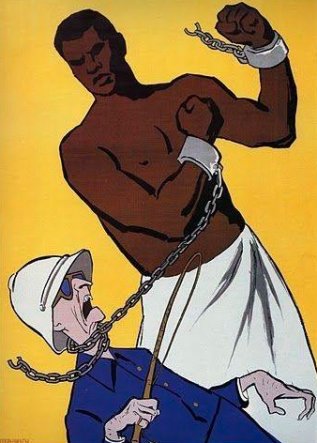

Despite the overwhelming power of the European colonisers, African resistance to colonisation was a continuous and defining feature of the era, far from a passive acceptance of foreign rule. It manifested in diverse forms, from fierce armed struggle to subtle acts of defiance. Early on, many African polities met invading European armies with military force, as seen in the Anglo-Zulu War, the resistance of Samori Ture in West Africa, the Ashanti wars, and the Maji Maji Rebellion against German rule in East Africa, often employing spiritual beliefs to rally forces. Though often outmatched by European weaponry, these campaigns demonstrated immense courage and a refusal to submit. Beyond military confrontation, resistance took other forms: diplomatic appeals to European powers (though rarely heeded), spiritual movements that sought to restore traditional ways of life, and later, the emergence of nascent nationalist movements, labour unions, and intellectual dissent among educated Africans. These efforts, though often suppressed, laid the groundwork for the eventual struggle for decolonisation in the mid-20th century.

Despite the overwhelming power of the European colonisers, African resistance to colonisation was a continuous and defining feature of the era, far from a passive acceptance of foreign rule. It manifested in diverse forms, from fierce armed struggle to subtle acts of defiance. Early on, many African polities met invading European armies with military force, as seen in the Anglo-Zulu War, the resistance of Samori Ture in West Africa, the Ashanti wars, and the Maji Maji Rebellion against German rule in East Africa, often employing spiritual beliefs to rally forces. Though often outmatched by European weaponry, these campaigns demonstrated immense courage and a refusal to submit. Beyond military confrontation, resistance took other forms: diplomatic appeals to European powers (though rarely heeded), spiritual movements that sought to restore traditional ways of life, and later, the emergence of nascent nationalist movements, labour unions, and intellectual dissent among educated Africans. These efforts, though often suppressed, laid the groundwork for the eventual struggle for decolonisation in the mid-20th century.