|

Berlin Conference

The Berlin Conference of 1884 essay and summary, including plenipotentiaries, the agreements reached and the full General Act text. After the formal unification of Germany in 1871 under the leadership of Otto von Bismarck, who installed Kaiser II as emperor and himself as Chancellor, Europe was hit by the Gründerkrise, a long period of economic depression. At this time, Bismarck was consolidating his power base and working towards establishing a war-free Europe, something largely achieved until 1914. With Europe and the Americas in the economic doldrums and whilst wanting peace in Europe, leaving no room for further continental expansion and simultaneously wanting to establish the prestige of the new Germany, Bismarck turned his attention to Africa as a potential field of influence, source of cheap resources and potential trade. | |

|

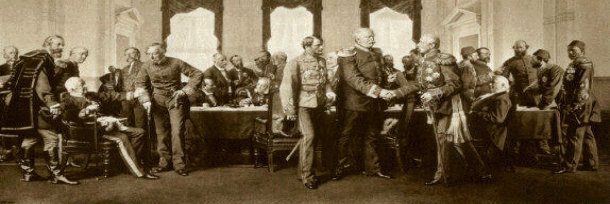

In part, this was also motivated by a desire to outflank King Leopold II of Belgium who was keen to establish his own empire in Africa. As such, he convened the Berlin Conference in November 1984 and invited fourteen states, including the USA, but not a single African one, to divide up the African continent and establish an agreed set of rules for the future exploitation of the continent, with France, Germany, Great Britain, and Portugal being the major players. What was hoped to be achieved at the Berlin Conference was primarily the establishment of a framework for the orderly partition of Africa, aiming to prevent open warfare among the European powers themselves. The conference laid down rules, most notably the principle of "effective occupation," which meant that a mere claim to territory was insufficient; a power had to demonstrate effective control, establish administration, and utilise the land economically.

It also declared freedom of navigation on the Congo and Niger rivers and banned the slave trade (though the reality of forced labour in many colonies was little better). Beyond these formal rules, each participating European power hoped to secure strategic territories, access to resources, and markets to bolster its national economies and international standing. Ideologically, many Europeans genuinely believed in a "civilising mission" – a paternalistic conviction that they were bringing Christianity, Western education, and "progress" to supposedly "backward" peoples, often cloaking the underlying motives of exploitation and domination in moral righteousness.

The immediate achievement of the Berlin Conference was the formalisation and legitimisation of the partition process. It didn't start the Scramble, but it provided the legal and political roadmap for its completion. In the decades following, particularly from 1885 to 1914, the continent was systematically carved up. Great Britain, driven by figures like Cecil Rhodes and the vision of a "Cape to Cairo" railway, acquired vast territories stretching from Egypt to South Africa, alongside significant holdings in West and East Africa. France consolidated its control over a massive expanse of West Africa, North Africa (Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco), and Madagascar. Germany, late to the colonial game, nonetheless secured significant territories in Togo, Cameroon, German East Africa, and German South West Africa. Portugal, leveraging historical claims, maintained its grip on Angola and Mozambique. Italy seized Eritrea and Italian Somaliland, later adding Libya. By 1914, only Liberia and Ethiopia (Abyssinia) remained independent – a testament to the comprehensive nature of the partition.

|