|

Scramble for Africa | Scramble for Africa | Scramble for Africa | Scramble for Africa |

|

|

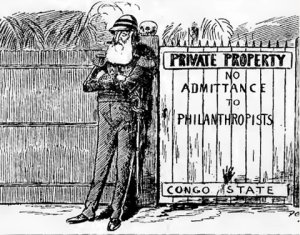

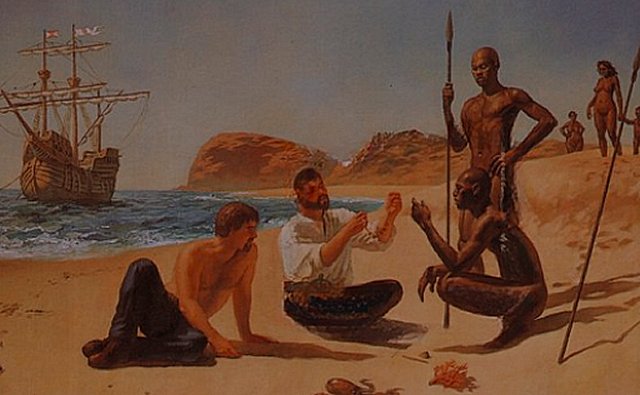

Industrial Revolution and Economic Imperatives: Europe's burgeoning industrial economies demanded vast quantities of raw materials – rubber, timber, minerals (gold, diamonds, copper), and agricultural products like cotton and palm oil – which Africa possessed in abundance. Furthermore, newly industrialised nations sought captive markets for their manufactured goods and lucrative investment opportunities. Technological Advancements: Innovations such as steamships dramatically reduced travel time, allowing easier access to Africa's interior via its rivers such as the Zambezi, which was then not only fully accessible, but open to the transport of bulk materials. Additionally, the development of quinine provided a defence against malaria, a major impediment to earlier European penetration. Crucially, military superiority afforded by the Maxim gun and other advanced weaponry gave European forces an overwhelming advantage against indigenous forces and resistance. Political Rivalry and National Prestige: The rise of powerful new states like a unified Germany and Italy, alongside established empires like Britain and France, fuelled intense nationalistic competition. Acquiring colonies became a symbol of national power, status, and strategic advantage, with each nation vying to outmanoeuvre its rivals. Acquiring colonies offered strategic advantages – coaling stations for naval fleets, control over vital trade routes like the Suez Canal (opened in 1869) – and a means to prevent rival nations from gaining too much influence. This highly competitive environment meant that a perceived threat of another nation claiming territory often spurred rivals to stake their own claims. Furthermore, there emerged ideological justifications for the Scramble for Africa. Social Darwinism, a pseudo-scientific theory applied Darwinian concepts of "survival of the fittest" to human societies, suggesting that European dominance was a natural outcome of their supposed racial and cultural superiority. Then there was what was known as the "Civilising Mission" (Mission Civilisatrice), with Europeans often rationalising their actions as a moral duty to "civilise" what they perceived as "backwards" or "savage" African societies. This mission encompassed introducing Christianity, European education, medicine, and forms of governance, often disregarding or actively suppressing existing African cultures and institutions. The economic depression that gripped Europe from 1873 to 1896 further intensified this search for captive markets and profitable ventures abroad. A pivotal moment, often described as an accelerant, was King Leopold II of Belgium's personal acquisition and brutal exploitation of the Congo Basin (bottom, left). His formation of the 'International Association of the Congo' and his private mercenary force, which operated with extreme brutality to extract rubber and ivory, sent shockwaves through European capitals, igniting fears that a single power could monopolise vast swathes of resources and strategic territory unless clear rules were established. It was this potent mixture of economic ambition, technological superiority, nationalist pride, and the very real prospect of inter-European conflict over African territories that led Otto von Bismarck, the Chancellor of Germany, to convene the Berlin Conference in 1884-1885. Ironically, Bismarck himself was initially ambivalent about colonial ventures, considering them a costly distraction. However, he recognised the need to manage the escalating tensions. The main plenipotentiaries at this momentous gathering represented Great Britain, France, Germany, Portugal, Belgium, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden-Norway, Austria-Hungary, Turkey, Russia, and the United States. Crucially, not a single African representative was invited or present. Cont/... Page I Page II Page III Page IV |