|

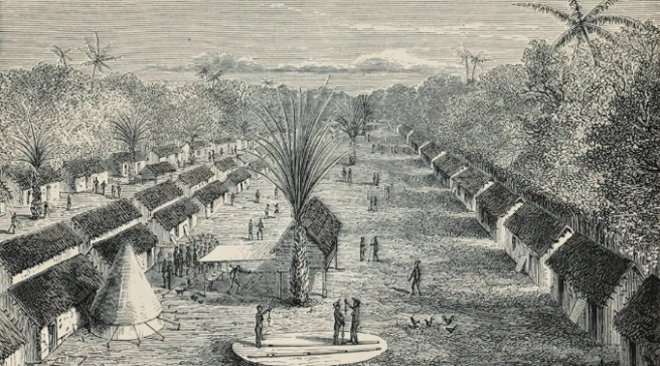

They established highly organised political structures based on divine kingship and a complex system of appointed governors. This model influenced the emergence of numerous powerful states within Zambia’s borders, most notably the Bemba Kingdom in the north and the Lunda Kingdom of Kazembe in the east. In the south, another great power emerged: the Lozi Kingdom of Barotseland (above, right). Founded perhaps as early as the 17th century, the Lozi developed a sophisticated feudal society adept at managing the annual flood cycle of the Zambezi River on the vast Barotse Floodplain. Their king, the Litunga, commanded a centralised state with a complex bureaucracy. By the early 19th Century Shaka, the Zulu leader, was making conquests around the south of Africa, expanding his empire. One displaced tribe fled north and in turn founded the Kololo Kingdom in what had been up until then the Lozi Kingdom of Upper Zambezi. Another tribe, the Ngoni, similarly fled Shaka's territorial ambitions and settled in east Zambia. These kingdoms were not isolated, instead integral parts of vast intercontinental trade networks, exchanging ivory, copper, and later, slaves, for goods such as cloth, beads, and firearms from the Swahili coast of East Africa and, later, with Portuguese traders from Mozambique. This period definitively refutes the colonial myth of an "empty land"; pre-colonial Zambia was a region of innovation, trade, and complex political organisation. By this time Europeans were active around Africa however, being landlocked and far from the ocean, what was to become Zambia did not have contact with them until the 18th century when explorer David Livingstone arrived in the area in 1851. He set up up a mission in the Kololo Kingdom, however it eventually failed after most of the missionaries died and his aim of replacing the slave trade with a cotton trade had a similar fate as no practicable trade route could be established through Mozambique.

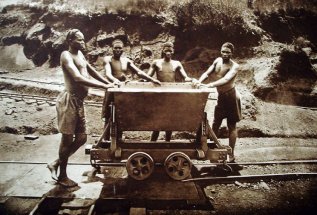

By the end of the 19th Century, modern day Zambia comprised North-Western Rhodesia (mainly the old Kingdom of Lozi which had been retaken from the Kololo in the 1860s) and North-Eastern Rhodesia. They were administered as separate territories until 1911 when they amalgamated to form Northern Rhodesia. By 1923 the British Government had not renewed the British South African Company's charter to work the area (having decided that 'company rule' was no longer appropriate) and it became a British crown protectorate. Two years later a legislature was formed, but the structures of oppression remained with the system of "indirect rule" often corrupting traditional authorities. Within the decade vast copper deposits had been found in the region that would become the Copperbelt in the 1920s (right), transforming the territory given it triggered massive labour migration, drawing men from rural areas across Northern and neighbouring Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) to work in the mines. This disrupted traditional societies and cemented a racially segregated economic system where the profits flowed overwhelmingly to European shareholders and settlers, while African workers faced harsh conditions, low wages, and systemic discrimination. By the outbreak of World War II, tens of thousands were employed in the industry however the advent of trade unionism started the process of antipathy and more latterly hostility to British rule. |

Zambia History |

Zambia History |

Zambia History | Zambia History |

Explore all about the African nation of Zambia in profile articles, pictures, videos and images.

More >

|

|

|

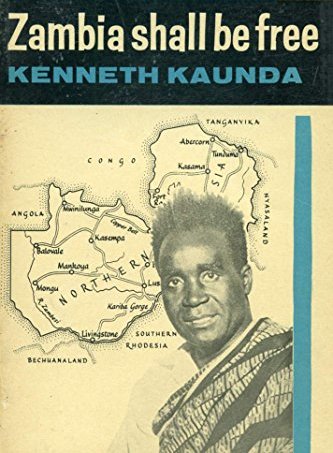

The whites in Northern Rhodesia (present day Zambia), Southern Rhodesia (present day Zimbabwe) and Nyasaland (present day Malawi) concluded that the 'blacks' would be easier to manage if the three colonies merged. Despite efforts through-out the 1940s by the whites for unification, a process vigorously opposed by the black majority, the colonial government in London accepted a compromise in 1953 by creating the Central African Federation (see infographic, below), also known as the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. This compromise entailed each of the three colonies having its own government but with a federal government overseeing foreign affairs in addition to matters that affected two or more of the colonies within the federation. This Federation, which lasted from 1953 to 1963, was deeply unpopular as it was widely seen as a device to entrench white minority rule, funnelling Northern Rhodesia’s copper wealth to benefit Southern Rhodesia, further embedding economic exploitation and political marginalisation. For example by the late 1950s, white workers were earning on average 2,071UK a year whilst black workers earned just 203UK a year, further sowing the seeds of a powerful nationalist movement. By 1960 pressure for the end of colonial rule was widespread across Africa. In that year Kenneth David Kaunda, a close friend of the colonial governor, established the United National Independence Party (UNIP) and, together with Harry Nkumbula of the African National Congress (ANC), mobilised widespread civil disobedience, including protests and strikes. Kaunda’s UNIP, which advocated for a unified nation across tribal lines, eventually became the dominant force. The struggle was largely peaceful, characterised by a philosophy of "positive non-violent action," though the colonial authorities often met protests with arrests and violence. The British government, under pressure, finally dissolved the Federation on 31st December 1963 and agreed to independence for Northern Rhodesia.

Kaunda’s early years were focused on unifying the country’s 73 ethnic groups under a single national identity, encapsulated in the slogan "One Zambia, One Nation" and his government invested heavily in education and healthcare, achieving significant social progress. However, the economy remained dangerously dependent on copper with the crash of copper prices in the mid-1970s devastating the nation, leading to decades of economic hardship. Kaunda’s initially humanist socialist policies gradually gave way to a one-party state as political repression increased in the face of growing economic problems and dissent. By 1991, pressure for change was overwhelming and Kaunda was forced to call multi party elections. Led by the Movement for Multi-Party Democracy (MMD) and its leader, Frederick Chiluba, Zambia embraced a return to multi-party politics with Frederick Chiluba becoming president that year with 81% of the presidential election vote. His party, the Movement for Multi-party Democracy (MMD), took 125 out of the available 150 seats. To his credit, Kaunda was only the second of Africa's presidents to step down, marking a pivotal return to democracy. Chiluba was re-elected in 1996, however with growing disillusionment of his rule mired with allegations of corruption and incompetence in dealing with the floods and drought that affected two million Zambians in 2001, the MDC split with many of its members breaking away to form the Forum for Democracy and Development. Unable to seek a third term in office, Chiluba was succeeded by former Vice President Levy Mwanawasa who went onto win a second term in 2006. However he died in office within two years and was succeeded by his vice-president Rupiah Banda who narrowly went on to win his own mandate later that year. He was defeated by opposition leader Michael Sata of the Patriotic Front in the September 2011 presidential election, but died in London on 28th October 2014, being succeeded by his Vice-President Guy Lindsay Scott until a presidential by-election could be held on 20th January 2015. Scott was the first white president of Zambia and was succeeded by Edgar Chagwa Lungu, the country's former Minister of Justice and Minister of Defence, who served as the sixth president of Zambia since 25 January 2015 until he lost the 2021 election to long-time opposition leader Hakainde Hichilema. As such, post-independence, Zambia has solidified its democratic credentials, though not without challenges as the nation continues to grapple with issues of economic diversification, poverty alleviation, corruption, and managing its immense national debt. |

The colonial period began in earnest in the late 19th century, inextricably linked to the "Scramble for Africa" and the figure of Cecil John Rhodes. Rhodes' British South Africa Company (BSAC) received a charter to exploit mineral resources north of the Zambezi and through a combination of deceitful treaties and military force, the BSAC claimed the territory, with its economy built on two pillars - land expropriation and mineral extraction.

The colonial period began in earnest in the late 19th century, inextricably linked to the "Scramble for Africa" and the figure of Cecil John Rhodes. Rhodes' British South Africa Company (BSAC) received a charter to exploit mineral resources north of the Zambezi and through a combination of deceitful treaties and military force, the BSAC claimed the territory, with its economy built on two pillars - land expropriation and mineral extraction.

The following month saw Kuanda elected as Prime Minister of Northern Rhodesia, an event which led to the country's full independence from the UK on 24th October 1964 as the Republic of Zambia, with himself as its first president. The nascent country was named after the Zambezi River, a powerful symbol of a new national identity free from its colonial past.

The following month saw Kuanda elected as Prime Minister of Northern Rhodesia, an event which led to the country's full independence from the UK on 24th October 1964 as the Republic of Zambia, with himself as its first president. The nascent country was named after the Zambezi River, a powerful symbol of a new national identity free from its colonial past.