|

| Britain | France | Belgium | Portugal | Italy | Other | Not Colonised |

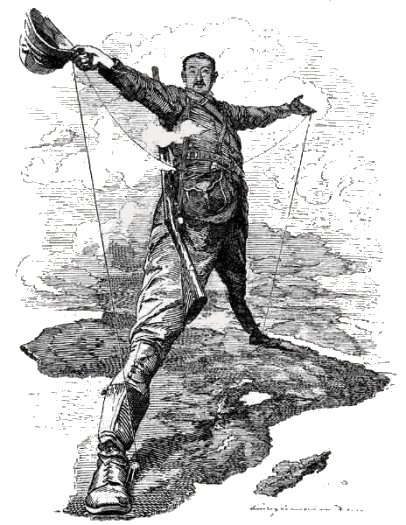

At first glance, the modern political map of Africa reveals an intriguing tapestry of nations, some with remarkably straight, almost geometric borders that traverse vast landscapes. These lines, often appearing to defy geographical logic, are not the result of organic historical evolution or natural divisions. Instead, they are the indelible imprints of a brutal, transformative period in history: the European "Scramble for Africa" during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The colonial map of Africa is far more than just a historical artefact; it is a living blueprint that has profoundly shaped the continent's political, economic, and social realities, with repercussions that resonate to this day. Prior to European colonisation, Africa was a continent of immense diversity, home to thousands of distinct ethnic groups, languages, and complex political systems, ranging from vast empires like the Zulu Kingdom and the Ashanti Empire to decentralised communities. European engagement before the 1880s was largely confined to coastal trading posts. However, a confluence of factors - including the Industrial Revolution's demand for raw materials and new markets, burgeoning European nationalism, and technological advancements like quinine (combating malaria) and steamboats - ignited an aggressive race for territorial acquisition. |

Colonial Map of Africa |

Colonial Map of Africa |

Colonial Map of Africa | Colonial Map of Africa |

|

Colonial Map of Africa

The rapid and chaotic nature of this land grab prompted concerns among European powers that their competing claims would lead to interstate conflict. To prevent this, German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck convened the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885. This pivotal, albeit deeply controversial, gathering saw fourteen European nations (and the United States, which did not participate in the partitioning) meet to formalise the rules of African colonisation. Crucially, no African representatives were present at this conference, despite their continent being the sole subject of discussion. The Berlin Act, signed at the conference, established the principle of "effective occupation," meaning a colonial power had to demonstrate actual control over a territory, not just claim it, to legitimise its claim. This spurred a frantic dash to establish administrative outposts, military garrisons, and economic ventures across the continent. The result was the arbitrary carving up of Africa into some 40 new colonies and protectorates, with little to no regard for existing indigenous boundaries, cultures, or geographical realities. The defining characteristic of the colonial map of Africa is its artificiality. European cartographers, often thousands of miles away, drew lines on blank or poorly detailed maps, frequently using rulers and compasses. These lines rarely respected natural geographical features or, more critically, the established socio-political structures that had governed African societies for centuries. The colonial map of Africa is not merely a historical curiosity but a powerful reminder of a period of profound external intervention that sculpted the continent into its current form. While African nations have made immense strides since independence, addressing the challenges born from these inherited borders – fostering national unity amidst diversity, building robust democratic institutions, and achieving equitable economic development – remains a central task. Understanding the origins and characteristics of these lines is crucial to comprehending the complex dynamics of modern Africa and its ongoing journey of self-determination and growth. The earliest map of Africa is believed to have been created in 1389 and is called the "Da Ming Hun Yi Tu" (above) which shows the continent as part of a wider map of the Ming Dynasty. Created in silk it shows Africa more than a hundred years before the first western explorers from Portugal started to chart parts of Africa's coastline. The map appears to show Lake Victoria and the River Nile. |