|

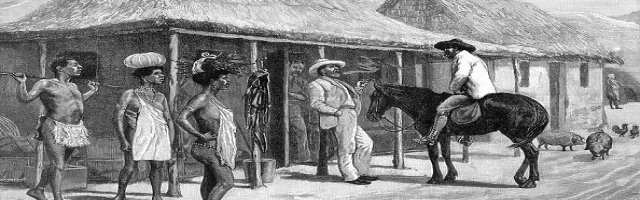

Following the Anglo-Boer Wars (1880-1881, 1899-1902), which saw both the British and the Boers exert influence over Swaziland, its fate was ultimately sealed. The British emerged victorious in the Second Anglo-Boer War, and in 1903, the British High Commissioner for South Africa assumed jurisdiction over Swaziland. This was formalized in 1907 with the establishment of Swaziland as a British Protectorate, effectively bringing direct colonial rule. The colonial period was characterized by the marginalization of Swazi traditional authority and the imposition of a Western administrative system. Much of the land had been alienated to European settlers, leading to widespread landlessness among the indigenous population. A key figure during this period was King Sobhuza II (r. 1899–1982), who, though a child when he ascended the throne, embarked on a lifelong mission to regain lost lands and restore full sovereignty to his people. He received a Western education, traveled extensively, and through persistent diplomatic efforts, including an appeal to the Privy Council in London, he slowly began to restore the Swazi people’s economic and political standing. He founded the Swazi National Fund (Tibiyo Takangwane) in 1968, a unique institution designed to hold mineral and land rights in trust for the nation, distinct from the government, thereby ensuring the preservation of the Swazi birthright. |

Eswatini History |

Eswatini History |

Eswatini History | Eswatini History |

|

|

On September 6, 1968, Swaziland achieved its independence, with King Sobhuza II as the head of state. Initially, the country adopted a Westminster-style parliamentary constitution. However, King Sobhuza II, believing that this constitution was alien to Swazi culture and encouraged divisive party politics, abrogated it in 1973. He declared a state of emergency, dissolved parliament, and vested all legislative, executive, and judicial power in himself, with the parliament being relegated to having a mere advisory role comprising both the monarch's nominees and candidates nominated by local councils (Tinkhundlas). This move marked the beginning of Eswatini’s distinctive political system: an absolute monarchy, where the king rules by decree. Despite this, Sobhuza II’s reign, which lasted 82 years, was a period of relative stability and cautious modernization. He focused on nation-building, economic development, and preserving Swazi culture while engaging with the international community. After King Sobhuza II's death in 1982, a period of regency followed, marked by some political instability as various factions vied for influence. In 1986, HRH Prince Makhosetive was crowned King Mswati III. His reign has continued the tradition of absolute monarchy, emphasizing national unity, cultural preservation, and economic development.

The king's appointed prime minister Prime Minister, Barnabas Sibusiso Dlamini (in office from October 2008 to September 2018) said that the government will consider using 'sipakatane' to "punish dissidents and foreigners who come to the country and disturb the peace" (this being a form of torture where the feet are repeatedly hit with nail embedded rods.) He was succeeded by Vincent Mhlanga who died on 24th December 2020 from Covid who was in turn succeeded by his deputy Themba Masuku who drew widespread criticism for his handling of the 2021 Eswatini Protests against the monarchy. On 16th July 2021, King Mswati replaced Masuku with Cleopas Dlamini as the new prime minister until 28 September 2023. Mgwagwa Gamedze then served as acting Prime Minister of Eswatini from that date until 4 November 2023 when he was succeeded by Russell Dlamini, the former CEO of the National Disaster Management Agency who remains in office to this day. Economically, Eswatini faces significant challenges, including high levels of poverty, unemployment, and a devastating HIV/AIDS epidemic that has severely impacted its social fabric and economic productivity. The nation continues to rely heavily on its agricultural sector, particularly sugarcane, and revenue from the Southern African Customs Union (SACU). Efforts are underway to diversify the economy, attract foreign investment, and improve social indicators. A significant marker in Eswatini's recent history occurred in 2018, when King Mswati III announced the country's name change from Swaziland to Eswatini, coinciding with celebrations for 50 years of independence and his 50th birthday. The name "Eswatini" is the pre-colonial name for the country, meaning "land of the Swazis," representing a reclamation of its indigenous identity and a symbolic break from its colonial past. |

The Dlamini clan, the progenitors of the modern Swazi nation, were part of this wave. They arrived in the area around the early to mid-18th century, settling initially near the Pongola River.

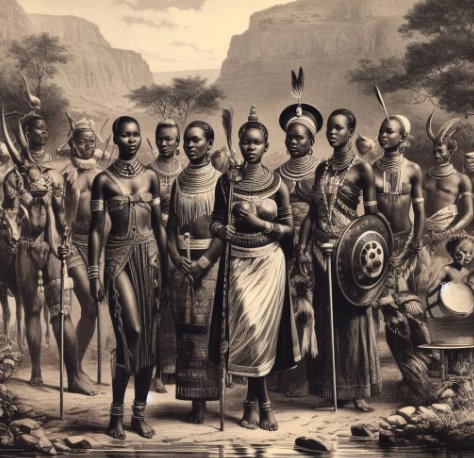

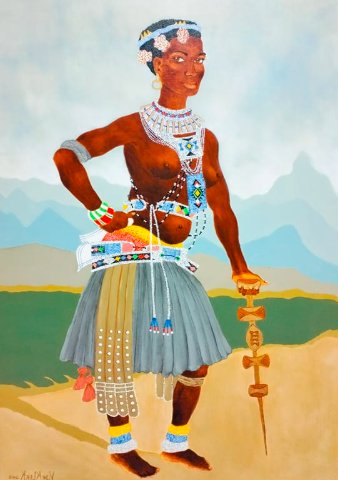

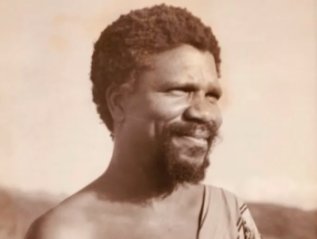

The Dlamini clan, the progenitors of the modern Swazi nation, were part of this wave. They arrived in the area around the early to mid-18th century, settling initially near the Pongola River. The true genesis of the Swazi nation is often attributed to Ngwane III (r. c. 1745–1780, left), who is considered the first king of a unified Swazi people. He led his followers northwards, establishing their core territory in southern Eswatini, laying the groundwork for the future kingdom. His successor, Sobhuza I (r. c. 1800–1839), proved to be an even more pivotal figure. Faced with the turbulent Mfecane (or Difaqane), a period of widespread chaos and warfare in Southern Africa triggered by the rise of the Zulu Kingdom under Shaka, Sobhuza I adopted a strategic approach. Rather than engaging in direct, often devastating, military confrontation, he forged alliances through diplomacy, marriage, and absorption of smaller clans, consolidating his authority and expanding the Swazi domain. His leadership was instrumental in preserving the Swazi identity and laying the architectural foundations of a cohesive nation, complete with a powerful monarchy and a well-defined cultural framework.

The true genesis of the Swazi nation is often attributed to Ngwane III (r. c. 1745–1780, left), who is considered the first king of a unified Swazi people. He led his followers northwards, establishing their core territory in southern Eswatini, laying the groundwork for the future kingdom. His successor, Sobhuza I (r. c. 1800–1839), proved to be an even more pivotal figure. Faced with the turbulent Mfecane (or Difaqane), a period of widespread chaos and warfare in Southern Africa triggered by the rise of the Zulu Kingdom under Shaka, Sobhuza I adopted a strategic approach. Rather than engaging in direct, often devastating, military confrontation, he forged alliances through diplomacy, marriage, and absorption of smaller clans, consolidating his authority and expanding the Swazi domain. His leadership was instrumental in preserving the Swazi identity and laying the architectural foundations of a cohesive nation, complete with a powerful monarchy and a well-defined cultural framework.

The mid-20th century witnessed a wave of decolonisation across Africa, and Swaziland was no exception. Under the astute leadership of King Sobhuza II, the path to independence was carefully managed. Rather than adopting an adversarial stance, Sobhuza II worked within the British system, forming political parties such as the Imbokodvo National Movement (INM) which championed Swazi traditional values and gradual change. This strategy proved highly effective, securing a smooth transition.

The mid-20th century witnessed a wave of decolonisation across Africa, and Swaziland was no exception. Under the astute leadership of King Sobhuza II, the path to independence was carefully managed. Rather than adopting an adversarial stance, Sobhuza II worked within the British system, forming political parties such as the Imbokodvo National Movement (INM) which championed Swazi traditional values and gradual change. This strategy proved highly effective, securing a smooth transition. The recent history of Eswatini under King Mswati III (right) been characterized by a complex interplay of internal dynamics and external pressures. While the monarchy remains deeply revered by many, there have been increasing calls for democratic reforms, particularly from pro-democracy movements and civil society organizations. These calls often center on issues of human rights, political freedom, and accountability, leading to periodic protests and international scrutiny, however all political parties still banned with regular outpourings of civil disturbances brutally put down by the regime. It has been described as "as an island of dictatorship in a sea of democracy" however King Mswati counters that the country is not ready for greater democracy believing that such democracy creates divisions and that, as a monarch, he is a strong unifying influence.

The recent history of Eswatini under King Mswati III (right) been characterized by a complex interplay of internal dynamics and external pressures. While the monarchy remains deeply revered by many, there have been increasing calls for democratic reforms, particularly from pro-democracy movements and civil society organizations. These calls often center on issues of human rights, political freedom, and accountability, leading to periodic protests and international scrutiny, however all political parties still banned with regular outpourings of civil disturbances brutally put down by the regime. It has been described as "as an island of dictatorship in a sea of democracy" however King Mswati counters that the country is not ready for greater democracy believing that such democracy creates divisions and that, as a monarch, he is a strong unifying influence.