|

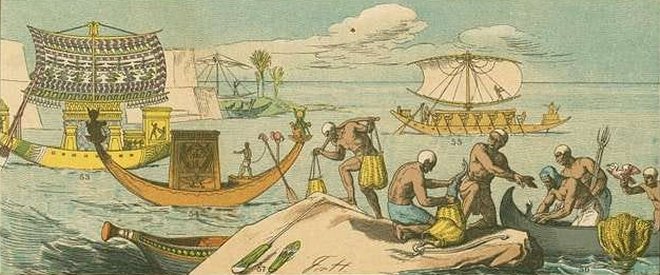

This arrival of Islam in the 7th century CE marked a profound turning point. Arab traders and missionaries traversed the Red Sea, introducing the new faith to the coastal communities. Over subsequent centuries, various Islamic sultanates, such as Ifat and Adal, emerged in the wider Horn of Africa region, extending their influence and control over the trade routes that passed through Djibouti's territory. These sultanates played a significant role in the spread of Islam and the development of distinct cultural identities among the Afar and Issa clans. The arid interior, however, remained largely the domain of pastoral nomads, whose fierce independence and traditional social structures persisted through centuries of external influence. The region's ports, though modest, facilitated the exchange of goods like frankincense, myrrh, salt, and spices, linking the African interior with the markets of the Middle East and beyond. The relative isolation of the region began to wane dramatically in the 19th century with the advent of European imperial ambitions, ushering in the colonial period. French interest in the area began with Rochet d'Hericourt's expedition of Shoa between 1839-42 and later expeditions by the French Consular Agent at Aden, Henri Lambert, and another by Captain Fleuriot de Langle. This interest was spurred to some degree by growing British influence in Egypt and led to a treaty of friendship between France and the Afar Sultans of Raheita, Tadjourah, and Gobaad who ruled parts of Djibouti in the nineteenth century. In 1862 the French consolidated their position with the purchase of Obock. Through a series of treaties signed with local Afar sultans and Issa clan chiefs between 1883 and 1887, France gradually acquired control over the territory, establishing a naval base at the anchorage of Obock, but soon shifted their focus to the more advantageous deep-water harbour of Djibouti City and in 1888 the French colony of Somaliland was established over the region. Cont/... |

Djibouti History |

Djibouti History |

Djibouti History | Djibouti History |

Explore all about the small nation of Djibouti on the east of Africa in pictures, videos and images.

More >

|

|

|

This colony of Somaliland broadly reflected Djibouti's current boundaries as marked out in 1897 by France and Emperor Menelik II of Ethiopia, at which time Ethiopia acquired parts of Djibouti. The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 had already transformed the Red Sea into a vital artery for global commerce and naval strategy, making the Horn of Africa a coveted prize for European powers and France, seeking to establish a coaling station and a strategic foothold to counter British influence in Egypt and Aden, turned its gaze towards the Gulf of Tadjoura. The new settlement of Djibouti City, which was made the colony's capital in 1892, quickly grew into a bustling port, particularly after the completion of the Franco-Ethiopian Railway in 1917 (left), Life under French colonial rule was characterised by the development of infrastructure aimed at facilitating trade and military operations, but also by the imposition of a foreign administrative system. While Djibouti City thrived as a multicultural port, attracting various communities including Yemeni, Indian, Greek, and Armenian traders, the interior remained largely untouched by French modernisation efforts. Tensions occasionally arose between the colonial administration and local populations, particularly concerning land rights and political representation. During both World Wars, Djibouti remained under French control, though its loyalty was tested during World War II when it initially sided with Vichy France before eventually aligning with the Free French forces. The post-World War II era saw a global wave of decolonisation, and Djibouti was not immune to these burgeoning nationalist sentiments. Calls for self-determination grew louder, fueled by political movements among both the Afar and Issa communities. France responded by making Djibouti an overseas territory within the French Union with its own legislature and representation in the French parliament, however calls for full independence continued to grow, complicated by Ethiopia who laid claim to the territory as they were eager for guaranteed access to the sea. Somalia had other ideas and envisioned a Greater Somalia uniting all Somali-speaking territories in the region. France, aware of Djibouti's continuing strategic importance and its economic ties to Ethiopia, sought to manage the transition carefully. Several referendums were held, the first in 1958, which saw the territory vote to remain a French Overseas Territory, largely due to the influence of pro-French Issa leaders and fears of domination by either Ethiopia or Somalia. A second referendum in 1967 also resulted in a vote to remain with France, though accusations of electoral irregularities and manipulation were widespread. French policies, which some critics argued favoured certain ethnic groups over others, further complicated the political landscape. Following this referendum, the territory was renamed as the French Territory of the Afars and Issas. Ten years later after the formation of the Ligue Populaire Africaine pour L´independance (LPAI), a unified political movement that led calls for independence, and under growing international pressure, France acknowledged the inevitable and negotiations commenced with the territory finally gaining its independence as the Republic of Djibouti on June 27, 1977. Following independence Hassan Gouled Aptidon, a prominent Issa leader, became the nation's first president, tasked with forging a unified national identity from a mosaic of clans and communities. Instead he installed a Issa led one-party state and continued to serve as president of the country until 1999 when he announced he would not be standing for a further term. Since independence, Djibouti has navigated the turbulent waters of regional geopolitics with remarkable resilience. Its strategic location continues to be its defining characteristic, attracting foreign military bases (French, American, Japanese, Chinese) and solidifying its role as a critical logistical hub. The port of Djibouti remains the primary maritime gateway for landlocked Ethiopia, driving much of the nation's economy. While facing challenges common to many developing nations, including economic diversification and resource scarcity, Djibouti has largely maintained stability, a rare feat in the often-volatile Horn of Africa, despiter its border disputes. |

which connected the Ethiopian highlands to the sea. Four years later in 1896 the territory was named French Somalialand and became a crucial strategic asset, serving as a vital naval base and a key hub for trade between Africa and the Middle East.

which connected the Ethiopian highlands to the sea. Four years later in 1896 the territory was named French Somalialand and became a crucial strategic asset, serving as a vital naval base and a key hub for trade between Africa and the Middle East.