|

Colonial Djibouti City |

Colonial Djibouti City |

Colonial Djibouti City | Colonial Djibouti City |

Explore all about the small nation of Djibouti on the east of Africa in pictures, videos and images.

More >

|

|

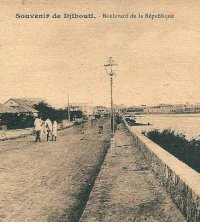

The administration's vision was one of efficiency and sanitation, a stark contrast to the unplanned settlements found elsewhere in the colonies. The city was initially divided into specialised zones. The Europeans and administrative offices occupied the high ground (notably the Plateau du Serpent, overlooking the sea), characterised by broad avenues, reinforced concrete structures, and architectural features designed to cope with the searing climate, such as verandas, large windows, and shaded arcades. This area housed the Governor's Palace, the barracks, and the main banking facilities, exuding stability and monumental colonial authority. In sharp contrast to the European quarter, the indigenous quarters were established closer to the port’s fringes and the inland periphery. These areas housed the majority of African, Arab (Yemeni), and Indian labourers and merchants who formed the backbone of the city's economy. While these quarters were essential for the city's operation, housing was often denser, materials less durable, and infrastructure - particularly sanitation - less advanced than in the French-occupied zones. This physical duality was a deliberate reflection of colonial social hierarchy, structuring daily life around enforced geographic divisions that governed access to resources and political power. Over time, key neighbourhoods like the Quartier Indigène evolved into vibrant, if spatially constrained, cultural melting pots, far more dynamic than the rigid formality of the European administrative centre. The absolute strategic purpose of Colonial Djibouti City, however, rested not with its architecture but with its role as the critical terminus of the narrow-gauge Chemin de Fer Franco-Éthiopien (CFE), or Ethio-Djibouti Railway (above). Construction of the railway began in 1897 by a French consortium under the auspices of the Imperial Ethiopian Company (CIE). Unfortunately, the company ran out of funds in 1906, leaving the partially completed railway coming to an abrupt halt in the middle of the Ethiopian desert. However, a remodelled company, the Franco-Ethiopian Railway Company (CFE), secured further funding by 1908, and the railway, which was originally planned to enhance trade from the Red Sea to Ethiopia, was finally completed in 1917 when it reached Addis Ababa. The railway was a monumental engineering feat and a linchpin of French imperial strategy as the railway would create a crucial trade artery linking Ethiopia’s rich interior to the global maritime routes, essential to dominating the region. It solidified Djibouti's position as the primary maritime outlet for landlocked Ethiopia, transforming Djibouti City from a simple outpost into the irreplaceable conduit for Ethiopian coffee, hides, and gold destined for Europe, and the entry point for manufactured goods, arms, and fuel flowing inland. The harbour itself rapidly developed, equipped with specialised quays, warehouses, and docking facilities necessary to handle the massive volume of transhipment. By the outbreak of World War I, Djibouti was firmly established as the dominant port in the Horn of Africa, outstripping its earlier rivals. The architectural legacy left by the early 20th century remains strikingly visible throughout the city centre. While the very earliest buildings relied on locally sourced coral stone, rapid advances in construction methods brought in imported materials. A distinctive utilitarian aesthetic emerged, blending elements of tropical functionality with strains of early Art Deco and Neoclassicism. Many of the long, low-slung administrative buildings, painted in the characteristic ochre or white, utilised deep, shaded walkways and natural ventilation systems - early responses to the unforgiving heat - that define the historical downtown area near the Place du 27 Juin. These structures speak volumes about the French preoccupation with creating a comfortable, yet distinctly non-local, environment for its expatriate population, while simultaneously imposing a bureaucratic order on the bustling port activities below. The colonial era was not without its moments of internal and external crisis. During the two World Wars, Djibouti City's strategic location elevated its importance. Post-1940, the territory of the French Somali Coast remained loyal to the Vichy regime, resulting in a tense blockade by Allied forces (primarily British) that severely curtailed the port’s economic activity until 1942, when the territory rallied to the Free French forces. This period of isolation underscored the city’s dependence on the sea lanes and the fragility of its singular economic model. The (above, left) video provides further insights into Colonial Djibouti City. |

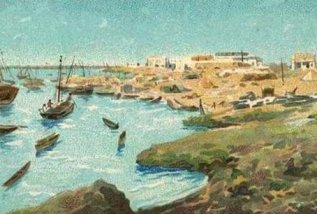

This marked the official beginning of French presence in Côte française des Somalis (French Somali Coast) that would eventually become French Somaliland. Initially a small, isolated outpost, Obock’s limitations soon became apparent. Its lack of a deep-water harbour across the Gulf of Tadjoura prompted the French to seek a more advantageous location for a major port and administrative centre, as well as one that was less exposed to attack.

This marked the official beginning of French presence in Côte française des Somalis (French Somali Coast) that would eventually become French Somaliland. Initially a small, isolated outpost, Obock’s limitations soon became apparent. Its lack of a deep-water harbour across the Gulf of Tadjoura prompted the French to seek a more advantageous location for a major port and administrative centre, as well as one that was less exposed to attack.