|

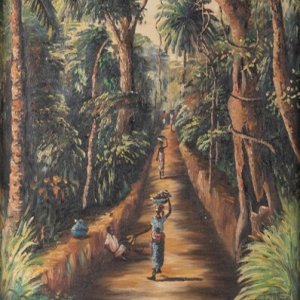

It was a marketplace where goods from vastly different regions converged. Canoe fleets, some masterfully operated by the Bobangi people (often called the "Vikings of the Congo"), would arrive from hundreds of kilometres upstream, their vessels laden with ivory, rubber, camwood powder, and foodstuffs. At the villages on the pool, these goods were traded with caravans that had travelled from the coast. This created a bustling economy where raffia cloth served as a form of currency and sophisticated trade networks flourished. The political landscape was decentralised, organised around village chiefs who held authority over their communities. While the area fell under the influence of the larger Teke Kingdom, daily life was governed by local customs and alliances with a society built on kinship, trade agreements, and a deep connection to the river that sustained it.

This new status triggered a wave of development, but it was development on strictly colonial terms with the defining feature of colonial Léopoldville being its stark segregation. First, there was the European town, known as La Ville. This was a carefully planned area with wide avenues, grand administrative buildings, spacious villas, and modern amenities like electricity and sanitation. It was the exclusive domain of the white colonial administrators, traders, and missionaries and the seat of power, order, and colonial authority. Separated from it, often by a neutral zone, was the Cité Indigène (the native city). This was where the Congolese population was forced to live. Comprised of neighbourhoods like Kinshasa, Barumbu, and Lingwala, this part of the city was often densely populated, poorly planned, and lacked the basic services afforded to the European sector. Movement between the two zones was heavily restricted, with curfews and a pass system (passeport intérieur) used to control the African population. Despite the oppressive system, the Cité Indigène became a dynamic and resilient space and, as Léopoldville grew into the colony's economic engine, it attracted Congolese people from all over the vast territory in search of work in the ports, factories, and as domestic servants. This migration turned the city into a multi-ethnic melting pot where new identities were forged. Within these crowded African quarters, a unique urban culture began to blossom. New forms of music, blending traditional Congolese rhythms with Latin American influences, laid the groundwork for the world-renowned Congolese rumba. It was a culture of creativity and adaptation, despite its people living under the weight of foreign rule. Independence in 1960 marked a new era, but one fraught with political instability. The city was a focal point of the Congo Crisis. In 1965 Joseph-Désiré Mobutu seized power in a coup and the following year as part of his "authenticité" campaign to shed colonial influences, renamed the capital as Kinshasa then, in 1971 the entire country as Zaire. Throughout Mobutu’s long rule and the subsequent Congo Wars, Kinshasa became a refuge for people fleeing conflict elsewhere in the country, leading to an uncontrolled population explosion that continues to shape the city today. This history of colonial ambition, post-independence hope, and protracted conflict is etched into the city's very fabric. Today, Kinshasa, with its city population of some 7.8m (with a wider metropolitan population of 17.8m, is a microcosm of the DRC with a population a rich tapestry of over 250 ethnic groups who have migrated from every corner of the vast nation, each bringing their own languages, customs, and traditions. While French is the official language of government and education, it is Lingala that truly unites the city. A fluid, expressive language, Lingala is the heartbeat of Kinshasa - the language of the streets, the markets, and most famously, the music. The Kinois, as the city's inhabitants are known, are defined by their resilience and resourcefulness. In a city with limited formal employment, survival depends on an entrepreneurial spirit known as "Système D" - the art of making do and finding clever solutions. This spirit is perhaps best embodied by the Sapeurs (Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes). These style connoisseurs turn the dusty streets into their runway, donning immaculate designer suits and accessories. La Sape is more than fashion; it’s a cultural statement of dignity, identity, and joy in the face of hardship. |

Kinshasa Profile |

Kinshasa Profile |

Kinshasa Profile | Kinshasa Profile |

Explore all about the Democratic Republic of Congo in a series of pictures, videos and images.

More >

|

|

|

A small formal sector comprising government institutions, embassies, banking, telecommunications, and the key administrative offices of the nation's vast mining interests can be found at Kinshasa's centre. Along the western edge of the central city, lies the industrial zone sector with the waterfront, along Kinshasa's northern edge, being lined with quays and large warehouses. The east of the city itself is home to the residential apartments for the elite class of Congolese and Europeans while poorer areas extend southward on the east and west of Kinshasa with satellites such as Ndjili, to the south-east, being a large residential area. This area is home to the city's sprawling informal economy, forming the city's true engine. It’s the street-side vendors selling everything from phone credits to fresh baguettes, the thousands of motorcycle taxis (wewa) weaving through traffic, the skilled artisans in the workshops, and the bustling markets like the famous Marché Central (Zando). For the majority of Kinois, the informal economy is not a choice but a necessity, a complex web of trade and services that provide a livelihood where formal jobs are scarce. The Congo River also remains a vital commercial artery, with barges carrying goods to and from the country's interior. Daily life in Kinshasa moves to a distinct rhythm. Mornings start with a city on the move, leading to legendary traffic jams (embouteillages) where vendors sell food, water, and household goods directly to drivers and passengers. The transport system itself is an adventure, from shared taxis to large, colorfully painted buses often humorously named "Spirit of Death" for their daring driving. More than anything, Kinshasa is synonymous with music. This is the undisputed capital of Congolese Rumba and its faster-paced derivative, Ndombolo. Music spills out from everywhere—homes, bars (ngandas), and taxis. There are may places to eat out in Kinshasa not least because the city is home to large expatriate communities meaning there is no shortage of quality restaurants serving meals to suit all tastes. We recommend you try, at least once, the local favourite 'Poulet a la Moambe', a local Congolese dish made from chicken, cassava leaves and palm butter served with ugali (millet and cassava flour). There are also many fish restaurants, perhaps obviously considering that the city borders the Congo River. Local beers include Simba and Bracongo (though be mindful beer in Africa is normally stronger than in the West.) Many street stalls offeri grilled goat (chèvre), fish wrapped in banana leaves (liboke), and staples like fufu (a dough made from cassava or corn flour) and pondu (cassava leaves). Kinshasa may look modern but, in reality, it was badly damaged by the years of conflict and many buildings are still in a state of disrepair and abandoned. The city centre is the only place with a reliable electricity and water supply with outlying areas subject to frequent power outages and breakdown of water supplies. Many of these outer areas of Kinshasa don't have even have paved roads, just dirt tracks, have frequent power cuts (délestage), inadequate clean water and sanitation systems, and potholed roads are daily realities. For visitors willing to look beyond the surface, Kinshasa offers unique and rewarding experiences: Other places of interest include Notre Dame Cathedral, and one of Kinsasha's most important religious buildings built in 1946 during the Belgian colonial rule and Eglise Ste Anne, the city's main Catholic church. The Kisantu Botanical Garden is also worth a look as is the 'Serpents du Congo', home to both venomous and non-venomous snakes. Generally Kinshasa is considered relatively safe but, as in any major conurbation, tourists and visitors should exercise caution especially when moving alone at night not least because there is widespread poverty in the city and many reports of muggings, pick-pocketing and other thefts. Kinshasa is also home to thousands of street children, known as 'Shegue', who have to rob, steal and harass to stay alive and numb their pain by taking drugs, entering into violent gangs and sniffing glue. Best avoided! The city’s rapid, unplanned urban sprawl strains housing and public services to their breaking point. High unemployment and poverty are persistent issues, and navigating the city requires a constant awareness of personal security. |

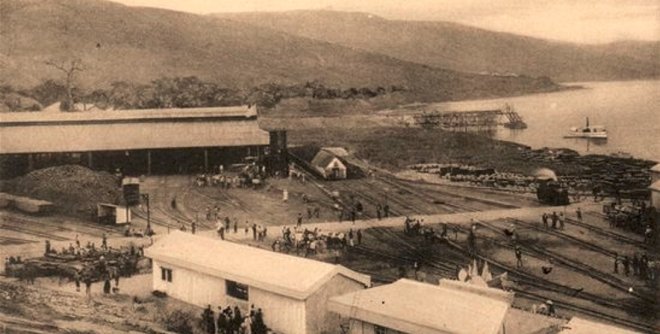

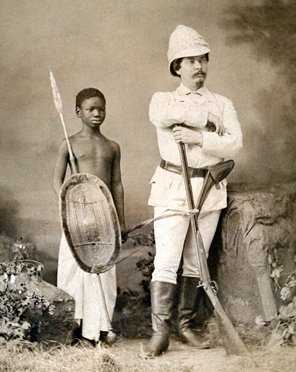

When explorer Henry Morton Stanley (left) arrived in 1877, he didn't discover an empty wilderness but a populated, well-organised collection of fishing and trading villages. Stanley established a trading post there and named it Léopoldville, in honour of his patron, King Léopold II of Belgium. On February 5, 1885, Belgian King Leopold II established the Congo Free State by brutally seizing the African landmass as his personal possession. Rather than control the Congo as a colony, as other European powers did throughout Africa, Leopold privately owned the region and the outpost rapidly grew into the administrative and commercial centre of his newly seized land spurred after a railway (above) connected it to the port of Matadi in 1898, making it the central hub for transporting the vast resources of the Congo’s interior to the outside world. At that time Léopoldville's population was a mere 5,000 people. Léopoldville then superseded Boma as the capital of the Belgian Congo in 1923 with its then population of 23,000.

When explorer Henry Morton Stanley (left) arrived in 1877, he didn't discover an empty wilderness but a populated, well-organised collection of fishing and trading villages. Stanley established a trading post there and named it Léopoldville, in honour of his patron, King Léopold II of Belgium. On February 5, 1885, Belgian King Leopold II established the Congo Free State by brutally seizing the African landmass as his personal possession. Rather than control the Congo as a colony, as other European powers did throughout Africa, Leopold privately owned the region and the outpost rapidly grew into the administrative and commercial centre of his newly seized land spurred after a railway (above) connected it to the port of Matadi in 1898, making it the central hub for transporting the vast resources of the Congo’s interior to the outside world. At that time Léopoldville's population was a mere 5,000 people. Léopoldville then superseded Boma as the capital of the Belgian Congo in 1923 with its then population of 23,000.