|

|

One of the most persistent questions about Kibera is its population. For years, media reports and even some NGOs have quoted a figure of "over one million people." This number has been powerful in attracting aid and attention, but is widely considered a significant overestimation. The official 2019 Kenyan Census recorded the population of Kibera at approximately 185,000 residents. While some argue that census takers may miss transient individuals or be met with distrust, this figure is far more aligned with academic studies and on-the-ground mapping projects than the one-million estimate. Regardless of the exact number, the population density is staggering. People from nearly every ethnic group in Kenya live there, packed into an area of just 2.5 square kilometres. This diversity creates a vibrant cultural melting pot but can also be a source of tension, particularly during times of political instability. |

Kibera Slum |

Kibera Slum |

Kibera Slum | Kibera Slum |

|

The slum today has few services. While many schools exist, most of them informal, they are normally under-resourced and overcrowded. Clinics are often overwhelmed by high rates of waterborne diseases like cholera and typhoid, as the slum just two main water points from a water treatment plant: one built by the Nairobi municipality and the other one by the World Bank. Clean water is therefore a precious commodity and sold by vendors from privately owned boreholes or government-rationed taps at a cost that is, per litre, often higher than what residents in affluent Nairobi neighbourhoods pay. The sanitation system is worse; a single latrine often shared on average by up to 50 shacks with the waste, when the latrines are full, being carried by children in what are known as "flying toilets" (waste disposed of in plastic bags), to the Motoine-Ngong River which now pretty much an open sewer and also badly polluted by tons of uncollected garbage generated in Kibera.

Kibera is hardly the place to bring up children, where one in five is dead before their fifth birthday, however as there are no contraception programs and it is estimated that at any given time half the women aged between 16-25yrs are pregnant and one in three children is an orphan. Many of these children inevitably end up on the streets. These children in Kibera are particularly vulnerable to abuse, having to either live alone or with other youths. It's a sad fact that solvent abuse, mainly glue, is rampant in the slum and often the children will walk into Nairobi to steal and pick pocket on the streets both to buy glue and have enough to buy the food that's available from small market stalls in Kibera. Daily life in Kibera starts early. The narrow, unpaved alleyways buzz with activity before dawn as residents begin their day with the sizzle of mandazi (a type of fried bread) being cooked at roadside stalls, and the hum of countless small-scale enterprises coming to life for, despite the immense challenges, Kibera is a hive of economic activity. The informal economy is not just a sideshow; it is the engine of the community. Every alleyway is lined with small businesses: kiosks selling groceries, barbershops, mobile phone charging stations, tailors, and workshops recycling scrap metal. Many residents work as casual labourers in Nairobi's industrial area or as domestic workers in nearby wealthy estates. This entrepreneurial spirit is a hallmark of Kibera. It is a place of immense ingenuity, where people find ways to survive and even prosper against incredible odds. The proliferation of mobile money services like M-Pesa has revolutionised commerce, allowing people to save, transfer money, and pay for goods securely without needing a formal bank account. Core issues remain for Kibera. Without legal ownership, residents live under the constant threat of eviction, and large-scale infrastructure investment is nearly impossible. However Kibera is home to hundreds of CBOs and NGOs working on everything from education and healthcare to youth empowerment and sanitation. These grassroots organisations are the lifeblood of positive change and initiatives like the Kenya Slum Upgrading Programme (KENSUP) have attempted to address the housing crisis by building modern apartment blocks. However such redevelopments have had unplanned for consequences. For example, when shanty homes have been razed to the ground, residents have lost their few worldy goods and they simply end up crammed into an existing neighbouring slum buildings. Despite attempts and the ceasless work of charities to improve the slum, one government official has stated that at the curent pace of progress, the relocation of Kibera's residents and redevelopment scheme will take 1,178 years to complete. |

As Nairobi grew, rural Kenyans flocked to the city seeking work but with formal housing being unaffordable, many found cheap, albeit illegal, lodgings in Kibera. When Kenya gained independence in 1963, the new administration viewed Kibera as unauthorised as the land tenure was never formalised, and the residents were considered "tenants at will". This lack of legal ownership was the single most critical factor shaping Kibera’s destiny as the government had no incentive to invest in infrastructure like sewage systems, roads, or clean water pipes.

As Nairobi grew, rural Kenyans flocked to the city seeking work but with formal housing being unaffordable, many found cheap, albeit illegal, lodgings in Kibera. When Kenya gained independence in 1963, the new administration viewed Kibera as unauthorised as the land tenure was never formalised, and the residents were considered "tenants at will". This lack of legal ownership was the single most critical factor shaping Kibera’s destiny as the government had no incentive to invest in infrastructure like sewage systems, roads, or clean water pipes.

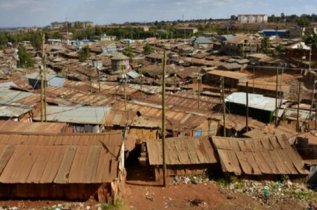

Residents of the slum typically live in homes made from a patchwork of corrugated iron sheets (known as mabati), timber frames, and mud walls and are normally about 12ft by 12ft, costing about six pounds a month to rent. A single room, typically occupied by eight people, often serves as a living room, bedroom, and kitchen for an entire family. Electricity, when available, is acessed through a complex and often dangerous web of illegal connections. Conditions are appalling with garbage and raw sewage spewing from every location making daily life hazardous especially for children who use these places as playgrounds. The stench from this rubbish and sewage is overwhelming and ever present. Without healthcare facilities many of these children die from diseases caught from the sewage. Malaria and HIV/AIDS are also rampant and life expectancy in Kibera is just 30 years.

Residents of the slum typically live in homes made from a patchwork of corrugated iron sheets (known as mabati), timber frames, and mud walls and are normally about 12ft by 12ft, costing about six pounds a month to rent. A single room, typically occupied by eight people, often serves as a living room, bedroom, and kitchen for an entire family. Electricity, when available, is acessed through a complex and often dangerous web of illegal connections. Conditions are appalling with garbage and raw sewage spewing from every location making daily life hazardous especially for children who use these places as playgrounds. The stench from this rubbish and sewage is overwhelming and ever present. Without healthcare facilities many of these children die from diseases caught from the sewage. Malaria and HIV/AIDS are also rampant and life expectancy in Kibera is just 30 years.