|

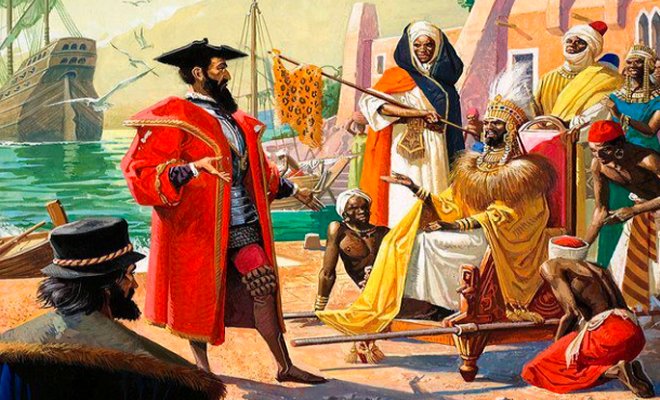

The arrival of the Portuguese in the 16th century briefly disrupted this equilibrium with their attempts to control trade routes, notably constructing Fort Jesus in Mombasa. However, their influence waned, giving way to Omani Arab dominance by the 18th century, which further entrenched the coastal trading economy and, tragically, the slave trade. The relative autonomy and vibrant commerce of the pre-colonial era dramatically shifted with the onset of the colonial period in the late 19th century. The infamous "Scramble for Africa," driven by European industrial ambitions and geopolitical rivalries, culminated in the Berlin Conference of 1884-85, which divided the continent without the consent of the Africans. Kenya fell under British influence, formally becoming the British East Africa Protectorate in 1895.

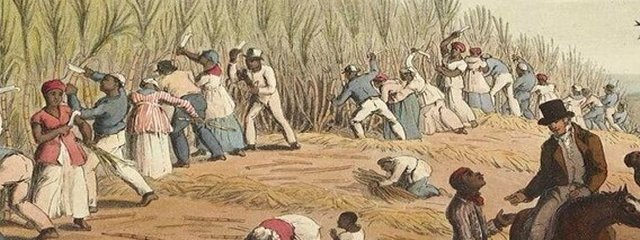

Once the railway was established, the British vision for the East Africa Protectorate, which became the Colony of Kenya in 1920 under the control of a British governor, shifted dramatically. The fertile highlands, with their temperate climate, were identified as ideal for European settlement. This led to one of the most painful and enduring legacies of colonialism: land alienation. Large swathes of the most productive agricultural land were seized from communities like the Kikuyu, Maasai, and Kalenjin and reserved exclusively for white settlers, creating the infamous "White Highlands." To ensure a steady supply of cheap labour for these new farms, the colonial administration imposed taxes, such as the hut tax, which had to be paid in cash. This forced Kenyan men to leave their homes and work for wages on European farms or public projects, fundamentally disrupting traditional economies and social structures. For colonial Kenya was built on a rigid racial hierarchy. At the top were the European administrators and settlers, who held all political and economic power. Below them were the Asians, primarily Indians, who were brought in to help build the railway and later became a commercial middle class. At the bottom were the African majority, who were largely denied political representation, access to quality education, and economic opportunities. Segregation was common in cities like Nairobi, with separate residential areas, hospitals, and schools for each racial group. Governance was often carried out through a system of "indirect rule," where British officials appointed local chiefs to enforce colonial policies, a move that often undermined traditional systems of leadership.

The second world war gave further impetus to the independence movement as hundreds of thousands of Kenyans fought side by side with white Europeans making them realise that the whites were by no means invincible. In 1944 the Kenyan African Union (KAU) was formed, dedicated to ending British rule and establishing Kenyan independence. In 1946 Kenyatta returned to Kenya after almost fifteen years abroad and soon thereafter assumed the leadership on the Kenya African Union. As the KAU's support grew and convened strikes, the police started firing on protestors to suppress the movement, but only fed the growing clamours for independence. |

Kenya History |

Kenya History |

Kenya History | Kenya History |

|

|

|

The Mau Mau rebellion was largely defeated by late 1956, with the capture of its most prominent leader, Dedan Kimathi, in October of that year, signaling the effective end of the "shooting war". However, the British only declared the state of emergency ended in 1960 and continued to hunt down remaining rebels for several years. During the rebellion 13,500 Africans were killed and over 30,000 men, women and children were held in concentration camps. While the British eventually suppressed the rebellion militarily, the high cost and international condemnation made it clear that colonial rule was unsustainable. Simultaneously the Kenya African National Union (KANU) and the Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU) both emerged in 1960 articulating the aspirations of different communities. Their charismatic leaders, Oginga Odinga and Tom Mboya together with Jomo Kenyatta, skillfully negotiated with the British through a series of Lancaster House Conferences, ultimately paving the way for a peaceful transition. Finally, on December 12, 1963, Kenya achieved that hard-won independence, with Jomo Kenyatta becoming its first President when the Republic was declared a year later. The initial years were marked by immense optimism and the ambitious goal of nation-building. Kenyatta's government introduced policies such as "Harambee" (Swahili for "pulling together"), encouraging self-help and collective effort for national development. There was a concerted effort towards Africanisation of the civil service and economy, and significant strides were made in education and infrastructure. However, the post-independence era was not without its challenges. Issues of land redistribution, ethnic balancing, and the consolidation of power soon emerged. KANU, the dominant independence party, steadily moved towards a de facto one-party state, centralising power and marginalising opposition voices. Upon Kenyatta’s death in 1978, Daniel arap Moi ascended to the presidency. His era, lasting until 2002, saw the formalisation of Kenya as a one-party state in 1982, characterised by increased authoritarianism, political repression, and economic stagnation. However, growing domestic and international pressure led to the repeal of Section 2A of the constitution in 1991, ushering in an era of multi-party politics. The 2002 general election marked a historic turning point when Mwai Kibaki's NARC coalition ended KANU's nearly four-decade rule. Kibaki's presidency saw significant economic growth and the introduction of free primary education, but it was also marred by intense political rivalries and the devastating post-election violence of 2007-2008, which exposed deep ethnic fissures within the nation. In response to this crisis, a new, progressive constitution was promulgated in 2010, introducing extensive reforms, including devolution of power and strengthened democratic institutions. Uhuru Kenyatta, the son of the first president, took office in 2013, overseeing the further implementation of the constitution, battling corruption, and navigating complex economic and social challenges. Today, Kenya stands as a vibrant, democratic nation, but one still grappling with the legacies of its past: the need for equitable land distribution, the ongoing fight against corruption, persistent ethnic divisions, and the crucial task of ensuring inclusive economic growth for its burgeoning youth population. Kenya's history is a testament to the enduring spirit of its people – a journey from the very origins of mankind to the intricate tapestry of a modern nation, forever striving towards a brighter, more equitable future. |

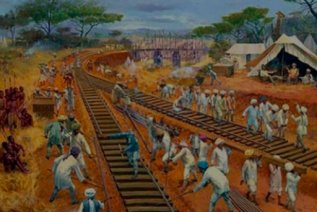

The new colony wasn't initially established for its own resources, but as a strategic corridor to the valuable lands of Uganda and the construction of the Kenya-Uganda Railway, dubbed the "Lunatic Express (right)". This railway was the true catalyst for British settlement and control, cutting a path through the interior to secure access to the fertile lands around Lake Victoria and beyond, opening it up for European influence and connecting the interior to the coast.

The new colony wasn't initially established for its own resources, but as a strategic corridor to the valuable lands of Uganda and the construction of the Kenya-Uganda Railway, dubbed the "Lunatic Express (right)". This railway was the true catalyst for British settlement and control, cutting a path through the interior to secure access to the fertile lands around Lake Victoria and beyond, opening it up for European influence and connecting the interior to the coast. Within a year of becoming a colony, dissent against British policies was beginning to fester led by Harry Thuku who helped found the Young Kikuyu Association and the East African Association before being arrested and exiled from 1922 to 1931. His arrest triggered a massacre outside Nairobi's Central police station in which twenty-three Africans were killed. This event probably marked the beginning of a concerted effort to achieve independence for the country. Jomo Kenyatta then became leader of the East African Association and later the secretary-general of the Kikuyu Central Association. In 1929 he went to the UK to make an abortive attempt to convince the colonial office that Kenya should be set free, however far from moves towards independence, Britain responded by convening the Carter Land Commission which concluded that permanent barriers should be in force between white-owned farms and reserves for Africans, which they needed permission to leave. Black outrage resulted in all African political associations being banned in 1940.

Within a year of becoming a colony, dissent against British policies was beginning to fester led by Harry Thuku who helped found the Young Kikuyu Association and the East African Association before being arrested and exiled from 1922 to 1931. His arrest triggered a massacre outside Nairobi's Central police station in which twenty-three Africans were killed. This event probably marked the beginning of a concerted effort to achieve independence for the country. Jomo Kenyatta then became leader of the East African Association and later the secretary-general of the Kikuyu Central Association. In 1929 he went to the UK to make an abortive attempt to convince the colonial office that Kenya should be set free, however far from moves towards independence, Britain responded by convening the Carter Land Commission which concluded that permanent barriers should be in force between white-owned farms and reserves for Africans, which they needed permission to leave. Black outrage resulted in all African political associations being banned in 1940.

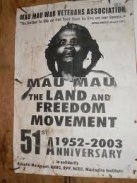

Kenya's most popular tribal group, the Kikuyu, led this clamour and formed the Mau Mau, a movement dedicated to overthrowing white dominance by whatever means required. The most prominent and defining moment of this struggle was the Mau Mau Uprising (1952-1956). Such were the levels of violence, not just against whites but the blacks who were considered white collaborators, a state of emergency was declared in Kenya in 1952 after Kenyatta and five colleagues were arrested. They were accused of organising the Mau Mau and subjected to seven years hard labour at a camp near Lake Turkana.

Kenya's most popular tribal group, the Kikuyu, led this clamour and formed the Mau Mau, a movement dedicated to overthrowing white dominance by whatever means required. The most prominent and defining moment of this struggle was the Mau Mau Uprising (1952-1956). Such were the levels of violence, not just against whites but the blacks who were considered white collaborators, a state of emergency was declared in Kenya in 1952 after Kenyatta and five colleagues were arrested. They were accused of organising the Mau Mau and subjected to seven years hard labour at a camp near Lake Turkana.