|

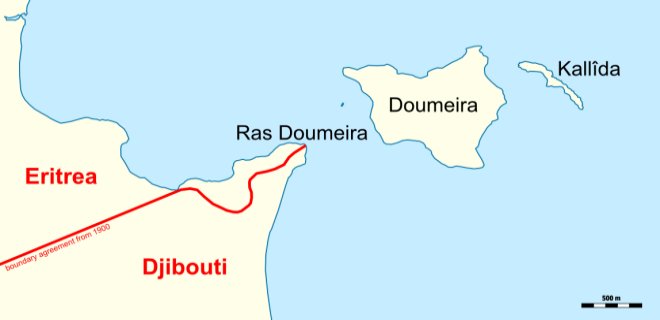

For decades, this ambiguity lay dormant. After Djibouti gained independence in 1977 and Eritrea in 1993, the border remained largely undefined but uncontested. Tensions first flared in 1996 when Eritrea accused Djibouti of involvement in the Hanish Islands dispute between Eritrea and Yemen, but the situation was defused. The underlying issue, however, was never resolved, leaving a geopolitical fault line waiting for a trigger. The direct cause of the 2008 war was a series of assertive actions by Eritrea starting in early April of that year. Eritrean forces crossed into the disputed Ras Doumeira region where they began building fortifications, dug trenches, and established a military presence on what Djibouti considered its sovereign territory. Djibouti’s government immediately protested, accusing Eritrea of unprovoked aggression and demanding an immediate withdrawal. The international community, including the Arab League and the United Nations, echoed these calls. Eritrea’s response was dismissive. President Isaias Afwerki denied the existence of any border conflict with Djibouti, stating that the issue was being fabricated by external forces, implicitly pointing a finger at the United States and Ethiopia, Eritrea's regional arch-rival. As diplomatic efforts failed and Eritrean troops refused to budge, the stage was set for a military confrontation given Djibouti might have been a small nation with a correspondingly small military, but hosted several foreign military bases, most notably a significant French contingent bound by a mutual defence treaty. The simmering tensions erupted into open warfare on June 10th, 2008. According to Djiboutian accounts, Eritrean soldiers deserted their positions and attempted to flee into Djibouti. When Djiboutian forces tried to assist them, they came under heavy fire from the remaining Eritrean troops. |

Djibouti Eritrea War |

Djibouti Eritrea War |

Djibouti Eritrea War | Djibouti Eritrea War |

Explore all about the small nation of Djibouti on the east of Africa in pictures, videos and images.

More >

|

|

|

What followed was a three-day battle characterised by intense artillery, tank, and machine-gun fire. The fighting was concentrated in the rugged, arid terrain around Ras Doumeira. Though vastly outnumbered, the Djiboutian army was better equipped and, crucially, received logistical, intelligence, and medical support from its French allies. French military aircraft conducted reconnaissance flights, and naval vessels patrolled the coast, providing a critical advantage. By June 13th, the fighting subsided into a tense ceasefire, with both sides reinforcing their positions. The conflict, though short, was sharp and bloody. The human cost of the three-day border war was significant for the scale of the engagement. Djibouti reported 44 of its soldiers killed and 55 wounded. Eritrean casualties were estimated to be much higher, with reports suggesting around 100 killed, many more wounded, and over 100 captured or deserted, however Eritrea, known for its tight control of information, never released official figures. The immediate outcome on the ground was a military stalemate. Eritrean forces remained in control of the disputed territory, but they had failed to advance further. The real outcome, however, shifted to the diplomatic arena. The United Nations Security Council strongly condemned Eritrea's actions, passing Resolution 1862 in January 2009. The resolution demanded that Eritrea withdraw its forces to the positions held before the conflict, acknowledge the border dispute, and engage in dialogue with Djibouti to find a peaceful solution. When Eritrea refused to comply, the UN imposed sanctions later that year, citing its role in the border conflict and its alleged support for militants in Somalia. The stalemate persisted until 2010, when Qatar stepped in as a mediator. In a major diplomatic breakthrough, Eritrea agreed to withdraw its troops from the disputed zone, and Qatar deployed a contingent of peacekeepers to monitor a demilitarised buffer zone. This arrangement effectively froze the conflict and brought a decade of relative stability to the border. Despite this, the fragile peace was shattered in 2017. Following the outbreak of the Gulf diplomatic crisis, which pitted Saudi Arabia and its allies against Qatar, both Djibouti and Eritrea sided with the Saudi-led bloc. In protest, Qatar withdrew its peacekeepers. Within hours, Eritrean troops moved back in and reoccupied Ras Doumeira and Doumeira Island. A dramatic regional realignment in 2018, centred on the historic peace agreement between Ethiopia and Eritrea, brought renewed hope. In September 2018, the leaders of Djibouti and Eritrea met in Saudi Arabia and agreed to normalise relations after a decade of hostility. While this was a monumental step, the fundamental issue - the formal demarcation of the border - remained unresolved. Today, the situation is quiet but uncertain. The Djibouti-Eritrea border war serves as a powerful case study of how colonial-era ambiguities, combined with modern geopolitical rivalries, can fuel conflict. While direct hostilities have ceased, the lack of a final, demarcated border means that the potential for future tension remains, a reminder that in the Horn of Africa, peace is often just the absence of war. |