|

The relative peace and self-governance of the pre-colonial era came to an abrupt end with the European "Scramble for Africa" in the late 19th century. French colonial expansion into the region began in earnest during the 1890s. French explorers and military expeditions encountered fierce resistance from the established kingdoms, particularly the Mossi. Moro Naba Wobgo of Wagadugu (right) famously resisted French encroachment, refusing to sign treaties that would cede his sovereignty. However, superior European weaponry and tactical advantages eventually led to the French conquest of the Mossi kingdoms and other territories by 1896. The French formally established their authority, initially incorporating the region into Upper Senegal and Niger. In 1919, a separate colonial entity named Upper Volta (Haute-Volta) was created, primarily carved out of territories from Upper Senegal and Niger and the northern part of Côte d'Ivoire with François Hesling as its first governor in response to fears of armed uprising against French colonial rule. This administrative division was driven by French strategic interests rather than existing ethnic or pre-colonial boundaries, setting the stage for future socio-political challenges. |

Burkina Faso History |

Burkina Faso History |

Burkina Faso History | Burkina Faso History |

|

|

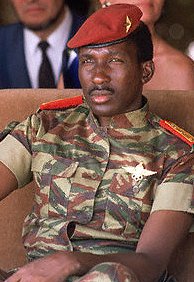

French colonial rule brought significant and often disruptive changes. Traditional political structures were dismantled or co-opted, with local chiefs repurposed as intermediaries for the colonial administration. The economy was reoriented towards serving French interests, with an emphasis on cash crops like cotton and the extraction of resources. Forced labour was widespread, used for building infrastructure such as roads and railways, and for agricultural projects. Perhaps one of the most enduring impacts was the massive forced migration of labour from Upper Volta to plantations and mines in other French colonies, particularly Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana, which significantly depleted the male population and disrupted family structures. In a controversial move, the colony of Upper Volta was dismembered in 1932 and its territory divided among Côte d'Ivoire, French Soudan (now Mali), and Niger. This decision was purportedly for economic efficiency but caused significant hardship and resentment among the populace. Popular demand and the recognition of the region's importance as a labour reservoir ultimately led to the re-establishment of Upper Volta as a distinct territory in 1947, albeit still under French control. The colonial period was marked, as ever, by economic exploitation, social disruption, and the imposition of a foreign administrative system, fundamentally altering the trajectory of the region. The aftermath of World War II saw a significant shift in the global political landscape and a burgeoning nationalist sentiment across Africa. The French colonies, including Upper Volta, In Upper Volta, political parties emerged, advocating for greater rights and eventually full independence. Key figures like Ouezzin Coulibaly and Maurice Yaméogo rose to prominence, mobilising popular support. The French government, facing increasing pressure and a changing international climate, gradually conceded more political freedoms. The Loi Cadre (Framework Law) of 1956 granted internal self-governance to French African territories, allowing for local assemblies and executive councils. In 1958, Upper Volta chose to join the French Community, moving towards greater autonomy while maintaining ties with France. However, the momentum for complete sovereignty was unstoppable. On August 5, 1960, Upper Volta achieved full independence, with Maurice Yaméogo becoming its first president. This pivotal moment marked the end of over six decades of colonial rule and ushered in a new era of self-governance, albeit one fraught with the challenges inherent in building a nation from scratch with institutions inherited from the colonial power. Soon after, Yaméogo banned all political parties apart from his own and he clung to power until a military coup in 1966 when he was deposed following a series of widespread demonstrations from students, unions and civil servants against the state of the country and living conditions. This became part of a pattern for the nascent nation, as the initial decades of independence for Upper Volta were characterised by political instability, economic struggles, and military coups. However, a defining moment came on 4th August 1983 in a further coup, sometimes referred to as the Révolution d'août or the Burkinabé revolution, carried out by radical elements of the army led by Thomas Sankara (above, right) and Blaise Compaoré, against the regime of Major Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo. This saw the rise of Captain Thomas Sankara, a charismatic and revolutionary leader who envisioned a radical transformation of the country. In 1984, as the President of the Republic of Upper Volta, Sankara dramatically renamed the country to Burkina Faso, a composite of words from two of the country's main indigenous languages: "Burkina" from the Moré language (meaning "upright" or "honest") and "Faso" from the Dioula language (meaning "fatherland"). The name "Land of Upright People" was a powerful symbolic break from the colonial past, a declaration of national pride, dignity, and a call for self-reliance and integrity. Sankara's government implemented ambitious programs aimed at social and economic development, including literacy campaigns, public health initiatives, and agrarian reform, profoundly shaping the national identity and fostering a sense of collective purpose. He remained in power until 15th October 1987 when, together with twelve other officials, he was killed in a further coup d'état organised by his former colleague Blaise Compaoré. Compaoré remained as president until his forced resignation in 2014. Today Burkina Faso is not considered a stable country, facing ongoing instability due to political turmoil, including recent coups in 2022, ongoing terrorist attacks, and worsening security conditions. A worsening security situation, climate shocks, and widespread socio-economic inequality have displaced millions, exacerbated poverty, and made access to essential services difficult. Check out the above video for more about Burkina Faso's history. |

The pre-colonial history of Burkina Faso is largely dominated by the rise and influence of the Mossi kingdoms (right), which emerged between the 11th and 13th centuries. According to oral traditions, these kingdoms were founded by warriors who migrated from the south (likely from present-day Ghana), conquering existing populations and establishing a highly centralised and militarised political system. The most prominent Mossi kingdoms included Wagadugu (Ouagadougou), Yatenga, Fada N'Gourma, and Tenkodogo.

The pre-colonial history of Burkina Faso is largely dominated by the rise and influence of the Mossi kingdoms (right), which emerged between the 11th and 13th centuries. According to oral traditions, these kingdoms were founded by warriors who migrated from the south (likely from present-day Ghana), conquering existing populations and establishing a highly centralised and militarised political system. The most prominent Mossi kingdoms included Wagadugu (Ouagadougou), Yatenga, Fada N'Gourma, and Tenkodogo. Beyond the Mossi, other groups like the Lobi in the southwest developed unique, decentralised social structures, characterised by a strong emphasis on individual autonomy and highly skilled ironworking. The Gurunsi also maintained powerful, though often smaller, chiefdoms. Each of these pre-colonial societies contributed to a rich cultural heritage, marked by elaborate spiritual beliefs (often animistic), complex initiation rites, vibrant artistic expressions including mask-making and sculpture, and sophisticated oral literature that served as both history and entertainment. This era was a testament to the ingenuity and resilience of the region's inhabitants, who forged complex societies and intricate networks long before the arrival of Europeans.

Beyond the Mossi, other groups like the Lobi in the southwest developed unique, decentralised social structures, characterised by a strong emphasis on individual autonomy and highly skilled ironworking. The Gurunsi also maintained powerful, though often smaller, chiefdoms. Each of these pre-colonial societies contributed to a rich cultural heritage, marked by elaborate spiritual beliefs (often animistic), complex initiation rites, vibrant artistic expressions including mask-making and sculpture, and sophisticated oral literature that served as both history and entertainment. This era was a testament to the ingenuity and resilience of the region's inhabitants, who forged complex societies and intricate networks long before the arrival of Europeans.

began to agitate for greater autonomy and self-rule. African leaders and intellectuals returned from Europe with new ideas of self-determination, and the experience of serving in the war had broadened horizons for many.

began to agitate for greater autonomy and self-rule. African leaders and intellectuals returned from Europe with new ideas of self-determination, and the experience of serving in the war had broadened horizons for many.