|

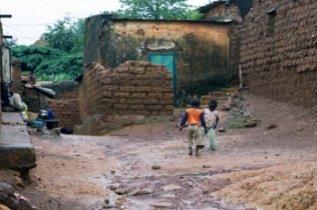

This home, or 'concession', is the cornerstone of Burkinabè society, particularly in these rural areas. These are not single-family houses in the Western sense, but rather communal compounds of several small, circular or rectangular mud-brick structures with thatched or corrugated iron roofs, often clustered together and surrounded by a mud and brick wall that serves as a courtyard. This open space is the heart of family life - a place for cooking, socialising, and raising children under the watchful eye of the extended family. In urban areas, housing is more varied, ranging from simple concrete block homes and rented rooms to more modern dwellings for the affluent. Regardless of the structure, the concept of family extends far beyond the nuclear unit, creating a powerful social safety net. Government staff in rural areas, such as teachers and nurses, are often provided with concrete block homes with corrugated tin roofs. Electricity and running water are generally not available, although some enterprising villagers attempt to charge batteries from solar panels and the odd gas fridge can be seen. |

Life in Burkina Faso |

Life in Burkina Faso |

Life in Burkina Faso | Life in Burkina Faso |

|

|

Despite this, rural electrification in Burkina Faso is a priority for the government which is overseeing a rapidly increasing access rate, though it remains low compared to urban areas. As part of this, the country is implementing a National Rural Electrification Strategy using the national grid, solar mini-grids, and standalone systems. Initiatives like the Yeleen Project and the Africa Minigrids Program are key, leveraging abundant solar resources to provide clean and affordable power to off-grid rural communities and foster economic growth. As with so many other countries in West Africa, the daily routine of fetching water takes up a fair share of the day with villagers often having to walk many miles to open wells and hand-pumped boreholes (many of which are out of service due to a lack of maintenance and funding) to collect water in plastic buckets and dishes. Again, improving access to clean water and improving the management of rural water points are ongoing priorities, addressed by government efforts with support from organizations like UNICEF, WaterAid, and the World Bank. However, while progress has been made, many rural communities still lack basic latrines and safe water sources, contributing to a cycle of disease and poor health. The Burkinabè diet is the heart of the nation’s agricultural backbone, built upon staple grains that can withstand the arid climate. The most common meal is Tô, a dense paste made from millet, sorghum, or maize flour, typically served with a variety of sauces, often prepared from local vegetables like okra, baobab leaves, or peanuts, and sometimes with a small amount of meat or fish when finances allow. Food security remains a persistent challenge as life in Burkina Faso is reliant on rain-fed agriculture, and the country is highly vulnerable to drought and climate change, which can lead to poor harvests and widespread food shortages, directly fuelling poverty. Employment and economic opportunities reflect the country's developmental stage. Agriculture is the largest employer, with most families engaged in subsistence farming, cultivating crops like millet, sorghum, and groundnuts for their own consumption. Cotton, sesame, and shea nuts are key cash crops, but fluctuating global prices and environmental factors make this a precarious livelihood. Formal employment is limited, concentrated in the public sector, foreign NGOs, and a small industrial sector, primarily in mining, as Burkina Faso is a significant gold producer. For many, particularly the youth, finding stable, well-paying work is a formidable challenge, limiting pathways out of poverty. Societal structures in Burkina Faso are deeply rooted in tradition, with ethnicity and family playing central roles. The country is home to over 60 ethnic groups, each with its own customs and languages, with the Mossi being the largest. Respect for elders is a paramount social value, and decisions are often made collectively within the family or community. This communal ethos is mirrored in the nation's religious landscape. Islam is the dominant faith, followed by Christianity, but these are often practised alongside deeply ingrained indigenous animist beliefs. This syncretism and a long history of religious tolerance have created a culture of peaceful coexistence, a source of national pride that has been tested by recent extremist violence. Despite this social cohesion, Burkina Faso faces immense systemic challenges, particularly in healthcare and sanitation. The healthcare system is critically underfunded and unevenly distributed, with most doctors and hospitals located in urban areas. Rural communities often rely on small, under-equipped health posts, and the cost of treatment can be prohibitively expensive for the average family. Consequently, treatable illnesses like malaria, respiratory infections, and diarrheal diseases are leading causes of mortality, especially among children. Access to traditional medicine remains a vital, and often the only, option for many. Life opportunities, especially for the younger generation, are intrinsically linked to education. While primary school enrollment has increased, significant barriers remain, including the cost of schooling, long distances to schools in rural areas, and a gender gap that sees fewer girls complete their education. For those who do graduate, the scarcity of jobs can be disheartening. The above video provides further insights into daily life in Burkina Faso. |

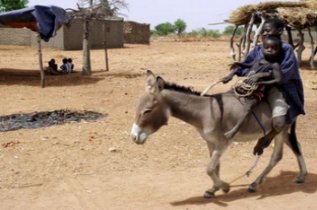

In contrast, in rural areas, life in Burkina Faso begins early with work in the fields and water collection, often from communal wells, predominantly undertaken by women and children.

In contrast, in rural areas, life in Burkina Faso begins early with work in the fields and water collection, often from communal wells, predominantly undertaken by women and children.