|

The arrival of the Portuguese navigator Diogo Cão (right) who was searching the area for gold in 1483 marked a pivotal turning point, ushering in the colonial era that would profoundly reshape Angola's history and destiny. The Portuguese encountered the Kingdom of Kongo (which covered modern day northern Angola) but also the Kingdom of Ndongoto its south which is believed to have been a separate kingdom subordinate to Kongo itself, but also ruled by a king, 'Ngola', from which Angola takes its name. Their conquests saw them proclaim a colony in Angola which was to last for four hundred years, though, in reality they did not exercise any actual administrative control over areas outside the coast until the twentieth century. Despite this, from the 16th to the 19th centuries, Angola became one of the primary sources of enslaved people for the Americas, particularly for Brazil as the Portuguese soon found finding slaves easier to trade and export to their colony there than their original objective of gold. Millions of Angolans were forcibly removed from their homes, tearing apart families and decimating communities. The insatiable demand for enslaved labour led to constant warfare as Portuguese forces and their local allies raided interior communities. This era was marked by fierce resistance from Angolan kingdoms, most notably by Queen Nzinga Mbande of Ndongo and Matamba in the 17th century, who waged a decades-long struggle against Portuguese encroachment, becoming a symbol of African defiance. By the late 19th century, with the "Scramble for Africa," European powers intensified their efforts to formalise their colonial possessions. Portugal, facing competition from other European nations, notably France and Britain, solidified its claim over Angola, expanding its territorial control beyond the coastal enclaves. This period saw the imposition of a deeply exploitative colonial administration. Forced labour, known as contratados or voluntários, became a cornerstone of the colonial economy, forcing Angolans to work on plantations and in mines under brutal conditions to produce cash crops like coffee and cotton, and extract minerals. Portuguese rule was characterised by systematic racial discrimination, limited access to education and healthcare for Africans, and the suppression of any form of political or cultural expression. Attempts at assimilation, through the Portuguese "assimilado" policy, touched only a tiny fraction of the population and did little to alleviate the pervasive oppression. |

Angola History |

Angola History |

Angola History | Angola History |

For information, videos and photos about the country of Angola, check out our Angola profile pages.

More >

|

|

|

This period of Agola's history saw the building of railways and ports together with towns and cities but little in the way of social development for the native population. In 1920 Angola became a colony with its own administration, and in 1952 Angola's status was changed from a colony to an overseas province. The mid-20th century witnessed the rise of fervent nationalist sentiments across Africa, and Angola was no exception. Despite severe repression by the Portuguese Estado Novo regime, which clung fiercely to its "Overseas Provinces," Angolan liberation movements began to emerge. Three main anti-colonial organisations led the charge, each with distinct ideological leanings, ethnic bases, and international alliances: Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (MPLA): Founded in 1956, it drew support primarily from the Kimbundu ethnic group and urban intellectuals, adopting a Marxist-Leninist ideology and receiving backing from the Soviet Union and Cuba. Frente Nacional de Libertação de Angola (FNLA): Emerging in the early 1960s, it was largely based among the Bakongo people in the north and was supported by the then Zaire (now Democratic Republic of Congo) and, at times, the United States. União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola (UNITA): Formed in 1966 by Jonas Savimbi, it primarily represented the Ovimbundu ethnic group in the central and southern regions, initially aligning with China and later receiving support from the United States and South Africa. A colonial war, often referred to as the Angolan War of Independence, erupted in 1961 and escalated into a brutal and protracted conflict. Portuguese forces, determined to hold onto their wealthiest colony, engaged in counter-insurgency operations, while the liberation movements waged guerrilla warfare across vast swathes of the country. The war raged for over a decade, claiming countless lives on all sides and leaving deep scars. The turning point came in April 1974 with the Carnation Revolution in Portugal, which overthrew the Salazarist dictatorship. The new democratic government in Lisbon swiftly announced its intention to decolonise its African territories. An agreement, the Alvor Accord, was signed in January 1975 between Portugal and the three Angolan liberation movements, aiming to establish a transitional government and hold elections. However, the deep ideological divisions, ethnic rivalries, and external interference (from South Africa, Zaire, the USA, Cuba, and the Soviet Union) quickly shattered the fragile peace. On November 11, 1975, Angola finally achieved its independence from Portugal, however this momentous occasion was immediately overshadowed by the outbreak of a devastating civil war. The three liberation movements, unable to share power, plunged the newly sovereign nation into one of the most protracted and bloody Cold War proxy conflicts. The MPLA, with significant Cuban and Soviet support, declared itself the legitimate government, while UNITA, backed by apartheid South Africa and the United States, and the FNLA, with Zairean and some US support, fought against it. The Angolan Civil War, which lasted for nearly three decades, was characterised by immense suffering. Millions were displaced, infrastructure was destroyed, and a generation grew up knowing nothing but conflict. The war became inextricably linked to regional conflicts, especially South Africa's apartheid regime, which sought to destabilise neighbouring states. The Bicesse Accord in 1991 was brokered to provide a path for democratic elections in Angola however when UNITA's Jonas Savimbi lost the election he deemed it fraudulent and returned to war. A further peace accord was signed in 1994 in Lusaka however this also failed. A massive military surge in 1999 by the Angolan military then decimated UNITA's forces however, even then, Jonas Savimbi continued guerrilla tactics until his death in 2002, a year that saw a de-facto cease fire and the end of a civil war that had seen the country broke down into factions leaving one and a half million dead, millions more displaced and the economy and the country's infrastructure shattered. The end of conflict allowed Angola to finally embark on the arduous path of national reconstruction. In the years since peace, Angola has witnessed significant economic growth, largely fueled by its vast oil reserves. The government initiated ambitious infrastructure projects, rebuilding roads, railways, and cities. However, the legacy of conflict, coupled with issues of corruption, inequality, and over-reliance on oil, continues to pose formidable challenges. The nation has also focused on diversifying its economy, strengthening democratic institutions, and addressing the social needs of its population. The short video documentary (above) explores the recent history of Angola during that troubled time. |

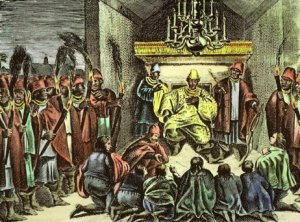

Initially, the Portuguese sought to establish diplomatic and trade relations with the Kingdom of Kongo. This led to the conversion of some Kongolese nobility to Christianity alongside the exchange of goods such as firearms and other technologies which the King of Kongo was more than happy to trade. In exchange, the Portuguese sought ivory and minerals, establishing trading posts in Ndono and a fortified Luanda in 1587 (above). However, this early interaction soon soured as the Portuguese grew increasingly interested in the region's human resources, spearheading the brutal transatlantic slave trade.

Initially, the Portuguese sought to establish diplomatic and trade relations with the Kingdom of Kongo. This led to the conversion of some Kongolese nobility to Christianity alongside the exchange of goods such as firearms and other technologies which the King of Kongo was more than happy to trade. In exchange, the Portuguese sought ivory and minerals, establishing trading posts in Ndono and a fortified Luanda in 1587 (above). However, this early interaction soon soured as the Portuguese grew increasingly interested in the region's human resources, spearheading the brutal transatlantic slave trade.