|

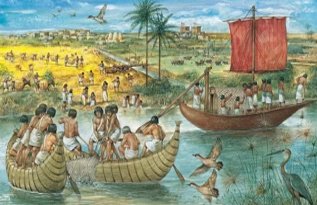

For ancient Egyptians, the river was not merely a source of water; it was the heart of their cosmos, a divine entity whose annual inundation dictated their existence. Without the River Nile's predictable floods, which deposited rich, fertile silt onto the parched desert lands, agriculture would have been impossible, and the Egyptian civilisation would probably never have taken root. Every year, from July to November, the River Nile would swell, peaking in September at around 20 feet, submerging its banks and transforming the narrow strip of cultivation into a vast, temporary lake. As the waters receded, they left behind a rejuvenated layer of black, nutrient-rich soil – the "Black Land" (Kemet), contrasting sharply with the "Red Land" (Deshret) of the desert. This natural fertilisation allowed for abundant harvests of wheat, barley, and papyrus, sustaining a population that grew to be one of the largest and most sophisticated of the ancient world.

But the River Nile's influence extended far beyond Egypt. To the south, the ancient kingdoms of Nubia and Kush, with their own rich histories and powerful pharaohs, flourished along its middle reaches, often challenging or collaborating with their northern neighbours. Further upstream, various tribes and communities in modern-day Sudan, Ethiopia, and other East African nations developed unique cultures shaped by their proximity to the river's tributaries and floodplains. Although both the Greeks and Romans had set out to identify the source of the Nile, they were unable to move further south than the wetlands of south Sudan. It was during the colonial era, when European powers recognised the strategic and economic importance of controlling the river, leading to exploration and eventual competition for its resources, that this search started anew. The quest was aided by the introduction of steam ships lower down the river that made such expeditions more viable. Its discovery is now generally credited to John Hanning Speke (4th May 1827 - 15th September 1864), a British Indian army officer who 'discovered' Lake Victoria in 1858 and declared it the Nile's source, an event he confirmed in a later expedition in 1863 detailed in his book of that year "The Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile" published before he accidentally killed himself in a shooting accident the following year. Today, the source of the White Nile is believed to be in Burundi, as noted above. |

The River Nile |

The River Nile |

The River Nile | The River Nile |

|

The River Nile's utility has always been multifaceted, evolving with human ingenuity but remaining fundamentally tied to the sustenance of life. Agriculture remains its most crucial use. From the earliest shadufs and saqias (ancient water-lifting devices) to modern irrigation canals and sophisticated pump systems, the River Nile's waters have been meticulously managed to irrigate vast fields, feeding hundreds of millions. Cotton, rice, sugarcane, and a variety of fruits and vegetables thrive in the River Nile basin, forming the backbone of many regional economies. Transportation continues to be vital. While ancient barges have given way to modern cargo ships and passenger ferries, the River Nile remains a significant conduit for internal trade and tourism, particularly the popular river cruises between Luxor and Aswan in Egypt, offering breathtaking views of ancient monuments. The River Nile is also an indispensable source of drinking water for the majority of Egypt's and Sudan's populations, and a growing number of people in the upstream riparian states. Its waters are treated and channelled to urban centres and rural communities, meeting the needs of cities like Cairo and Khartoum. In the 20th century, hydropower generation emerged as a transformative use. The construction of the Aswan High Dam in Egypt (completed in 1970) was a monumental engineering feat, creating Lake Nasser, one of the world's largest artificial reservoirs. This dam not only provides a massive source of electricity for Egypt but also offers crucial flood control and significantly expanded irrigation capabilities, allowing for year-round cultivation rather than solely relying on the annual flood. Similarly, numerous other dams, both large and small, dot the River Nile basin, harnessing its power for national development. Beyond these major uses, the River Nile supports diverse fisheries, providing a source of protein and income for local communities, and its rich biodiversity makes it a vital ecosystem for countless species of flora and fauna. The cumulative impact of the River Nile on human settlement, economic development, and cultural identity is immeasurable. Its presence has dictated population distribution, with the vast majority of Egyptians and Sudanese living within a few kilometres of its banks. It fostered unique architectural styles, artistic expressions, and religious practices. Economically, the river has been the lifeblood of nations, enabling trade networks and supporting agricultural economies that sustained complex societies for millennia. Politically, the River Nile has often been at the heart of regional power dynamics, with control over its waters being a perennial source of contention and cooperation among riparian states. Today, the River River Nile faces unprecedented challenges, primarily driven by rapid population growth, climate change, and the increasing demands for water resources by all riparian nations. Population growth across the Nile Basin means that the per capita share of water is shrinking, intensifying competition. Egypt, historically assured of a significant portion of the River Nile's flow, is now facing increased demand from swiftly developing upstream countries. Climate change poses a severe threat. Changes in rainfall patterns, increased evaporation rates, and the potential for more extreme weather events (both droughts and intense floods) could significantly alter the River Nile's flow. Furthermore, rising sea levels threaten the low-lying Nile Delta in Egypt, a crucial agricultural region, with saltwater intrusion and coastal erosion. Perhaps the most significant contemporary issue is the development of hydropower infrastructure in the upstream countries. The prime example is the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the Blue Nile (above). Ethiopia views the GERD as a vital project for its economic development, providing much-needed electricity for its growing population and potential export revenue. However, Egypt and Sudan express deep concerns about the dam's filling and operational policies, fearing a reduction in their historic water shares, which could severely impact their agriculture, drinking water supply, and the operation of their own dams. This has led to years of complex, often tense, negotiations, highlighting the intricate politics of shared water resources. In response to these challenges, there has been a push towards water diplomacy and cooperation. The Nile Basin Initiative (NBI), established in 1999, aims to foster cooperation on the equitable and sustainable management of the River Nile's resources. While progress has been slow and often fraught with disagreements, the NBI represents a crucial framework for dialogue among the basin states. Other modern concerns include environmental degradation, such as pollution from agricultural runoff and industrial waste, which affects water quality and biodiversity, and the spread of invasive species that can disrupt aquatic ecosystems. Sustainable management strategies, including efficient irrigation techniques, wastewater treatment, and catchment management, are becoming increasingly critical to ensure the long-term health of the river. |

|

Beyond agriculture, the River Nile served as the primary highway of ancient Egypt. It facilitated trade, communication, and the movement of goods and armies, effectively unifying a long, slender kingdom that stretched for hundreds of miles. Temples, pyramids, and cities were built within easy reach of its banks, their very existence dependent on the river's bounty and its transportation capabilities. The annual flood cycle also underpinned the Egyptian calendar, their religious beliefs (with deities like Hapi, the god of the River Nile flood, and Osiris, associated with fertility and rebirth), and their social structure.

Beyond agriculture, the River Nile served as the primary highway of ancient Egypt. It facilitated trade, communication, and the movement of goods and armies, effectively unifying a long, slender kingdom that stretched for hundreds of miles. Temples, pyramids, and cities were built within easy reach of its banks, their very existence dependent on the river's bounty and its transportation capabilities. The annual flood cycle also underpinned the Egyptian calendar, their religious beliefs (with deities like Hapi, the god of the River Nile flood, and Osiris, associated with fertility and rebirth), and their social structure.