|

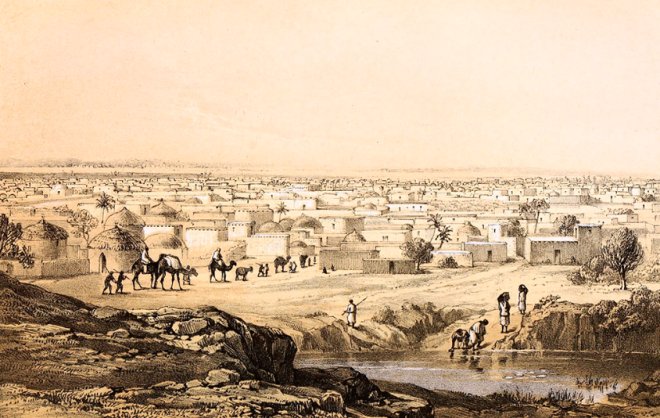

As the prehistoric era gave way, a multitude of sophisticated ancient kingdoms and empires emerged across the Nigerian landmass, each contributing to a rich tapestry of political, economic, and cultural development. These entities were defined by their complex social structures, advanced governance, and extensive trade networks. In the north, the Kanem-Bornu Empire, centred around Lake Chad, rose to prominence in the 9th century. Enduring for over a thousand years, it was one of Africa's longest-lasting empires, strategically positioned along critical Trans-Saharan trade routes. Its rulers, many of whom embraced Islam early on, fostered scholarship, established diplomatic ties, and maintained a powerful military. Further west, the Hausa city-states (such as Kano, Zaria, Katsina, and Gobir - image, above) flourished from the 11th century onwards. These independent but often allied city-states became vibrant centres of commerce, Islamic learning, and craft production, exchanging goods like gold, salt, kola nuts, and slaves with North Africa. Southwest Nigeria witnessed the rise of the Yoruba city-states, none more influential than Ife and Oyo. Ife, considered the spiritual homeland of the Yoruba people, attained its zenith between the 12th and 15th centuries, producing remarkably naturalistic bronze and terracotta sculptures that are among the finest examples of African art. The Oyo Empire, which emerged as a dominant power from the 14th to the 19th century, was characterised by its formidable cavalry and sophisticated political system headed by an Alafin. Its influence extended over a vast territory, exercising control through tribute and military might. To the southeast, the Kingdom of Benin, founded around the 13th century, grew into one of West Africa's most powerful states. Renowned for its magnificent bronze and ivory sculptures (Benin Bronzes), the kingdom developed a highly centralised political structure and controlled extensive trade routes, including early contact with European powers. In the eastern regions, distinct from the centralised kingdoms, Igbo societies developed complex, often decentralised, political systems characterised by democratic principles and village-level governance, though they also engaged in long-distance trade. These ancient civilisations showcase the indigenous capacity for self-organisation, economic prosperity, and artistic innovation long before external intervention.

European interest waned in the early part of the nineteenth century, however, when the Napoleonic Wars ended, Britain once again turned its attention to expansion within Nigeria with their focus shifting to raw materials as the slave trade diminished and industrialisation in Europe surged. Given its involvement in the area, The Berlin Conference of 1884 effectively rubberstamped the area as ripe for British control and development (although there were ongoing tensions with France over Nigeria's western border with French controlled Dahomey). Britain, driven by economic interests (palm oil, minerals) and strategic ambitions, then embarked on a systematic conquest of the diverse states and communities that would eventually form Nigeria. This was achieved through military expeditions against entities like the Benin Kingdom, the Aro Confederacy, and the Sokoto Caliphate, often with brutal force. Once completed, the British government established the Royal Niger Company in 1886, however revoked its charter on 1 January 1900 (paying them £865,000 incompensation together with rights to half of all mining revenue in a large part of the area for 99 years.) This arrangeement saw the territories of the Niger basin transferred to the British government and the Protectorates of Northern Nigeria and Southern Nigeria was formed. |

Nigerian History |

Nigerian History |

Nigerian History | Nigerian History |

For information, videos and photos of the West African nation of

Nigeria, check out our Nigeria pages.

More >

|

|

|

The landmark moment came in 1914 with the amalgamation of these two protectorates by Lord Frederick Lugard (below, right), creating the single geographical entity known as Nigeria. This artificial union, driven by administrative convenience rather than organic cohesion, brought together disparate ethnic groups with distinct histories, religions, and social structures under a single administration. British colonial policy, particularly in the north, relied heavily on "indirect rule," using existing traditional rulers as intermediaries to govern. The injustices and economic exploitation inherent in colonial rule inevitably fueled a growing desire for self-determination. The mid-20th century witnessed the rise of Nigerian nationalism, a powerful movement demanding an end to foreign domination and the restoration of sovereignty. Educated elites, many of whom had studied abroad and were exposed to Pan-Africanist and anti-colonial ideologies, spearheaded this movement. Key figures emerged to champion the cause of independence. Herbert Macaulay, often regarded as the "Father of Nigerian Nationalism," founded the Nigerian National Democratic Party (NNDP) in 1923. In the 1940s and 1950s, more robust political parties formed, reflecting regional and ethnic aspirations: the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC) led by Nnamdi Azikiwe, primarily popular in the Igbo-dominated east; the Action Group (AG) led by Obafemi Awolowo, strong in the Yoruba-dominated west; and the Northern People's Congress (NPC) led by Ahmadu Bello, representing the Hausa-Fulani majority in the north. These nationalist leaders, through petitions, protests, and political organising, pressured the British authorities for constitutional reforms. A series of conferences and revised constitutions (such as the Richards Constitution of 1946, the Macpherson Constitution of 1951, and the Lyttleton Constitution of 1954 which made the colony the autonomous Federation of Nigeria) gradually granted more legislative powers to Nigerians. Despite internal tensions regarding regional autonomy and the distribution of power, the collective aspiration for a unified, sovereign Nigeria prevailed. The demand for complete self-rule became irresistible. Finally, after decades of struggle and negotiation, Nigeria achieved its long-awaited independence from British rule on October 1, 1960. The Union Jack was lowered, and the Nigerian flag was hoisted, marking the dawn of a new era. The momentous occasion was celebrated with immense joy and optimism, as Nigerians embraced the challenge of nation-building. However, the legacy of the colonial past — particularly the arbitrary boundaries, regional imbalances, and ethnic rivalries that had been exacerbated by British administration — would continue to shape the political landscape of the newly independent nation, posing significant challenges for its future. Jaja Anucha Wachuku became the Nigerian Parliament's first black speaker after that independence (Wachuka was a close friend of USA Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy and Johnson.) Then, in October 1963, Nigeria became the Federal Republic of Nigeria with Nnamdi Azikiwe (left) as its first President. Within seven years the country's first Prime Minister had been assassinated, his successor killed in a counter-coup and a bloody civil war had broken out when three of Nigeria's eastern states seceded from the country in an attempt to establish themselves as the Republic of Biafra. Since that time, Nigeria's 250 ethnic/tribal groups have continued to provide not just powerful tensions in a multi layered society, tensions that even today spill over into religious violence particularly between Muslim and Christian communities with often fatal outcomes as many in Nigeria see themselves as belonging to an ethnic/religious groups rather than as a citizen of Nigeria itself. The three areas most Nigerians align themselves to are the Yoruba (westerners), Igbo (easterners) and Hausa (northerners). Explore Nigerian history further in the video (above). |

The arrival of European powers marked a significant turning point in Nigerian history, ushering in the colonial era that fundamentally reshaped the area's trajectory. Portuguese traders first made contact with the area in the late 15th century after they reached the mouth of the River Niger in 1470 and sent stories home of amazing African artefacts and the splendour of Benin's Oba or King (left). They engaged in trade that initially included goods like pepper and ivory, but soon escalated into the devastating transatlantic slave trade. For centuries, various European nations, primarily the British, exploited the region's human resources, leaving an indelible scar on modern-day Nigeria's social fabric and demography. From 1806 until the end of that century the British were busy exploring the area, charting its territory and rivers and preparing it for trade, mainly in palm oil which it was hoped would provide financial compensation for the loss of the slave trade that had seen millions of Nigerian shipped to America during the 16-18th centuries. (Ironically, local chiefs went on to enslave more Nigerians to meet the demand for this palm oil trade.)

The arrival of European powers marked a significant turning point in Nigerian history, ushering in the colonial era that fundamentally reshaped the area's trajectory. Portuguese traders first made contact with the area in the late 15th century after they reached the mouth of the River Niger in 1470 and sent stories home of amazing African artefacts and the splendour of Benin's Oba or King (left). They engaged in trade that initially included goods like pepper and ivory, but soon escalated into the devastating transatlantic slave trade. For centuries, various European nations, primarily the British, exploited the region's human resources, leaving an indelible scar on modern-day Nigeria's social fabric and demography. From 1806 until the end of that century the British were busy exploring the area, charting its territory and rivers and preparing it for trade, mainly in palm oil which it was hoped would provide financial compensation for the loss of the slave trade that had seen millions of Nigerian shipped to America during the 16-18th centuries. (Ironically, local chiefs went on to enslave more Nigerians to meet the demand for this palm oil trade.)

While seemingly efficient, this system often entrenched ethnic divisions, distorted traditional political structures, and ultimately served to exploit resources for the benefit of the British Empire. Infrastructure, such as railways, was developed primarily to facilitate the export of cash crops and minerals. Education was introduced, but often with missionary influence and limited scope, creating a small elite while neglecting mass literacy. The colonial period, despite some infrastructural developments, stifled indigenous economic growth, suppressed local industries, and imposed an arbitrary administrative framework that would have lasting consequences for the nascent nation. In 1922 a section of the German colony Kamerun was added to Nigeria under League of Nations mandate.

While seemingly efficient, this system often entrenched ethnic divisions, distorted traditional political structures, and ultimately served to exploit resources for the benefit of the British Empire. Infrastructure, such as railways, was developed primarily to facilitate the export of cash crops and minerals. Education was introduced, but often with missionary influence and limited scope, creating a small elite while neglecting mass literacy. The colonial period, despite some infrastructural developments, stifled indigenous economic growth, suppressed local industries, and imposed an arbitrary administrative framework that would have lasting consequences for the nascent nation. In 1922 a section of the German colony Kamerun was added to Nigeria under League of Nations mandate.