|

The school day is often marked by singing the Rwandan National anthem, "Rwanda Nziza" ("Beautiful Rwanda") followed by prayers in a country that is over 80% Christian with a much smaller Muslim population (4.6%). (Roman Catholic missionaries established themselves in Rwanda in the late 1880s and taught that Tutsi were a superior race ~ not least because they were easier to convert to Christianity ~ and this contributed to the seething ethnic tensions over the generations.)

There were 7,141 public primary schools in Rwanda as of 2022, with a total student enrollment of 2,410,750 who are taught in English or French (after starting their education in Kinyarwanda). According to UNICEF and government reports, primary school enrollment rates consistently hover above 95% however only 71% complete their primary education. Classrooms are often overcrowded, with approximately 56.14 students per teacher, according to data from TheGlobalEconomy.com, though this figure represents the ratio of students to teachers rather than the number of students per classroom. The curriculum is comprehensive, covering core subjects like Kinyarwanda, English (the primary language of instruction from primary four), Mathematics, Science, and Social Studies. Upon completing primary school, students progress to secondary education, also spanning six years. This stage is further divided into a three-year Ordinary Level (O-Level) (normally called 'Junior Secondary') and free, then, for some a three-year Advanced Level (A-Level) Normally reffered to as 'Senior Secondary' which has to be paid for. The secondary curriculum becomes more diverse, offering specialisations in sciences, humanities, and vocational streams, preparing students for higher education or direct entry into the workforce. Tertiary education encompasses universities, polytechnics, and vocational training institutions and Rwanda's gross enrollment ratio ratio is 6.5% for females and 8.1% for males according to the latest available figures. Enrollment in tertiary institutions has seen substantial growth, driven by government scholarships and the expansion of both public and private universities. The curriculum at this stage is designed to be responsive to market demands, fostering critical thinking, research skills, and practical competencies. Rwanda's youth literacy rate (ages 15-24) was 90% in 2022, a slight decrease from 92.5% in 2020 but compares with an adult literacy rate of 79.0% (2022), the last year for which figures are available.) When the school day concludes in the early afternoon, children in Rwanda embark on their journey home where they are expected to assist with household chores or help with agricultural tasks in the family's fields, whether it's weeding, planting, or harvesting crops like beans, maize, or cassava. For many families, subsistence farming is the primary source of livelihood, and every pair of hands contributes. |

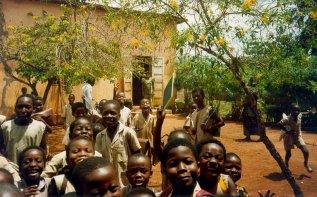

Children in Rwanda |

Children in Rwanda |

Children in Rwanda | Children in Rwanda |

For information, videos and photos of the African nation of Rwanda, check out our Rwanda pages.

More >

|

|

Despite these responsibilities, there is always time for play. Rwandan children are remarkably creative, often making their own toys from discarded materials – old tires become rolling vehicles, banana leaves transform into dolls, and sticks become swords or football goals. Football (soccer) is immensely popular, and makeshift pitches can be found everywhere, buzzing with energy and the shouts of young players. Traditional games, storytelling, and singing are also integral parts of their playtime, fostering strong social bonds and passing down cultural knowledge. There's a strong sense of community, and children frequently play together in multi-age groups, with older children often looking out for the younger ones. With limited access to electricity in many homes, activities in the evening often revolve around conversation, storytelling, and communal singing. Children learn about their family history, local legends, and moral lessons through these oral traditions. The concept of Umuco (Rwandan culture and values) is deeply ingrained, emphasising respect for elders (kubaha), community spirit (ubumwe), and hard work (umurimo). These customs shape their understanding of the world and their place within it, fostering a strong sense of identity and belonging. No discussion of daily life for children in Rwanda would be complete without exporing the enduring impact of the 1994 genocide. While there are no children in Rwanda today who witnesses the horrors of that genocide when around a tenth of the country's entire population was massacred including 300,000 children and young people, children born to parents who survived the genocide often inherit the psychological scars of their caregivers. Studies indicate higher rates of mental health issues such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety among survivors, which can subtly or overtly affect their parenting styles and the emotional environment of the home. Consequently, their children may exhibit similar symptoms, struggle with emotional regulation, or develop attachment issues, even without direct exposure to the trauma themselves. This inherited burden means many young Rwandans are navigating complex psychological landscapes shaped by a past they didn't live through. Beyond the individual psychological toll, the genocide irreparably altered societal structures. Many children grew up in single-parent or child-headed households, grappling with poverty and a lack of stable family support. The genocide saw a burgeoning use of unregulated orphanages with often poor standards of care. In response, the Rwanda government pledged to become the first nation in Africa to be orphanage-free, by adopting the 'Hope and Homes for Children' strategy used in much of eastern Europe at the time, where hundreds of institutions for children were closed down allowing the children to grow up in families instead, given 70% of orphaned children in Rwanda identified as still having living relatives following the genocide. Despite this initiative, many of the children ended up without adult carers, and today it is estimated there are around 3000 street children in Rwanada, primarily because of family poverty, the death of parents, the need to earn income for survival, juvenile delinquency, or mistreatment at home. Their situation and futures are further bighted by a lack of education, food, protection and health care access. The above video gives further insights into daily life for children in Rwanda where life expectancy is currently 67.78 years (2023). |

Following nursery for a limited few, although it's increasingly recognised for its crucial role in early childhood development, children in Rwanda enter the 12-year basic education program, which is free and compulsory. This encompasses six years of primary education, focusing on foundational literacy, numeracy, and general knowledge. Whilst most children in Rwanda are eager to attend education, many schools are under resourced with no running water nor electricity, although the government is attempting to get those schools too far from the national grid installed with solar panels to get over some of these difficulties. Rwanda's expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP for 2025 is not yet available, but the latest reported data is for 2023 (4.92%) or 2022 (4.75%). This compares favourably with neighbouring Uganda where spending is 2.55%.

Following nursery for a limited few, although it's increasingly recognised for its crucial role in early childhood development, children in Rwanda enter the 12-year basic education program, which is free and compulsory. This encompasses six years of primary education, focusing on foundational literacy, numeracy, and general knowledge. Whilst most children in Rwanda are eager to attend education, many schools are under resourced with no running water nor electricity, although the government is attempting to get those schools too far from the national grid installed with solar panels to get over some of these difficulties. Rwanda's expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP for 2025 is not yet available, but the latest reported data is for 2023 (4.92%) or 2022 (4.75%). This compares favourably with neighbouring Uganda where spending is 2.55%.

Food preparation is a communal activity in many Rwandan households, and children often participate in gathering ingredients or assisting with simple tasks. Dinner, typically the main meal of the day, is normally a staple of ugali (a thick porridge made from cassava or maize flour), matoke (cooked sweet bananas), sweet potatoes, beans, and various vegetables. Meat is consumed sparingly, often reserved for special occasions. Families often share from a single communal dish, using their hands to scoop the food. Children are taught to wait for elders to begin eating and to show appreciation for the meal. Nutritional challenges, particularly for very young children, still exist, and stunting remains a significant issue for under-five children in Rwanda, with a national average of 33% in 2020, although this represents a reduction from earlier years. To combat this, the Rwandan government established the Stunting Reduction Programme (SRP) in 2018, which is a multi-sectoral initiative focusing on integrated health, nutrition, and social protection services.

Food preparation is a communal activity in many Rwandan households, and children often participate in gathering ingredients or assisting with simple tasks. Dinner, typically the main meal of the day, is normally a staple of ugali (a thick porridge made from cassava or maize flour), matoke (cooked sweet bananas), sweet potatoes, beans, and various vegetables. Meat is consumed sparingly, often reserved for special occasions. Families often share from a single communal dish, using their hands to scoop the food. Children are taught to wait for elders to begin eating and to show appreciation for the meal. Nutritional challenges, particularly for very young children, still exist, and stunting remains a significant issue for under-five children in Rwanda, with a national average of 33% in 2020, although this represents a reduction from earlier years. To combat this, the Rwandan government established the Stunting Reduction Programme (SRP) in 2018, which is a multi-sectoral initiative focusing on integrated health, nutrition, and social protection services.