|

The daily life of children in Namibia is remarkably varied, sculpted by geographical location, socio-economic status, and cultural heritage. In rural areas, particularly in the northern regions where a significant portion of the population resides, a child's day often begins with the rising of the Sun. Chores are an integral part of growing up, instilling a sense of responsibility from a young age. Girls might assist with fetching water from communal boreholes or rivers, often carrying heavy containers for long distances, or help with cooking, housework, and caring for younger siblings as well as assisting their mothers pound flour into the ground then helping with the cooking itself. Boys frequently participate in herding livestock – cattle, goats, or sheep – a task that can take them far from home and teaches them about the land and its rhythms. Aother chores include helping to build and maintain homesteads, plough fields and other agricultural tasks.

Namibia has made significant strides in various sectors since gaining independence in 1990, yet persistent challenges remain. The country has a relatively young population, with approximately 36% of its populace under the age of 18, highlighting the importance of investing in its future. Healthcare for children has seen improvements, with infant and under-five mortality rates decreasing over the years, though they remain higher than desired in some regions. Key health challenges continue to include malnutrition, particularly in remote and drought-prone areas, and the prevalence of diseases such as HIV/AIDS – though significant progress has been made in prevention and treatment, especially for mother-to-child transmission. Malaria also poses a threat in certain northern regions. Access to clean water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) facilities varies widely, impacting child health and education, especially in rural schools and informal settlements where these amenities are often scarce or non-existent.

While enrollment rates are high, the quality of education can be inconsistent, especially in remote schools, which often lack adequate resources, trained teachers, and proper infrastructure. Long distances to school (many children have to walk several kilometres each way, often on empty stomachs, to reach their nearest school), coupled with a lack of reliable transportation, contribute to absenteeism and dropout rates. For children with disabilities, access to inclusive education remains a significant battle, with many facing barriers to attending school or receiving appropriate support. The transition from primary to secondary education, and subsequently to tertiary education or vocational training, is a bottleneck for many, limiting their future prospects. Education is comprised of Lower Primary (grades 1 - 4) and Upper Primary (grades 5 – 7), then, following a national exam, students can progress to Junior Secondary (grades 8 – 10) then Senior Secondary (grades 11 - 12) at the end of which successful students are awarded the Namibia Senior Secondary Education Certificate. A further bolster to education has been the recent introduction of pre-primary education aimed at children from poor backgrounds aged 5 and 6yr old. Literacy rates among youth (15-24 years old) are also high, often above 90%. |

Children in Namibia |

Children in Namibia |

Children in Namibia | Children in Namibia |

Explore all about the southern African nation of Namibia in articles, pictures, videos and images.

More >

|

|

Child protection issues are another grave concern. Despite legal frameworks, children in Namibia are vulnerable to various forms of exploitation and abuse. Child labour, though often informal, sees children engaged in activities like street vending, domestic work, or helping with agricultural chores, sometimes at the expense of their schooling and well-being. Sexual abuse, neglect, and violence in homes and communities are stark realities that many children face, often going unreported due to fear, stigma, or a lack of accessible reporting mechanisms. The issue of street children, particularly in urban centres, also highlights a segment of the child population facing extreme vulnerability. To address this, the government in Namibia ratified the Protocol of 2014 to the Forced Labour Convention however the practice is still widespread.

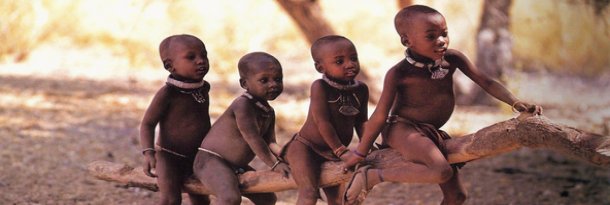

Most children in Namibia live within families engaged in farming even though half of the arable land in the country is owned by white farmers. Namibia is home to thirteen major tribes with the Bantu-speaking Ovambo or Owambo being the largest and they all have different languages and customs from being land-based, planting and harvesting maize, sorghum and 'mahangu,' a type of millet that is used for the staple meal of porridge, not to be mistaken with western porridge (well, after you've drunk it you certainly won't mistake the two!) while other tribes such as the Herero and Himba live lives around cattle and livestock with beef being the most favoured meat in the country. Other significant tribes include the Damara and the nomadic San Bushmen. There are also White Namibians; the Afrikaner, German, Swedish, British, and Portuguese.

Given the poor quality of the land, many adult males are migrant workers in urban areas or in the mines. Inevitably there is child labour and trafficking in Namibia, fuelled by poverty, the high number of orphans and others fleeing nearby Angola. This work includes agriculture, cattle herding, domestic work, and commercial sexual activity with San children being particularly vulnerable to forced labour on farms or in homes. In urban areas children can often be found working in shebeens (bars) or on the streets peddling candles, fruits, handicrafts, and cell phone air time vouchers. Finally, the impact of climate change is increasingly affecting Namibian children. The country is highly susceptible to droughts and floods, which devastate livelihoods, exacerbate food insecurity, and displace communities. Children are disproportionately affected by these environmental shocks, experiencing disrupted schooling, increased health risks due to contaminated water, and psychological distress. These climate-induced challenges add another layer of complexity to the already existing socio-economic vulnerabilities, threatening the hard-won gains in child welfare. The video above shows daily life for street children in Namibia. There are many charities you can contact to help children there together with child sponsor programs. |

In stark contrast, children in urban centres like Windhoek or Swakopmund often experience a more modern existence. While chores are still present, they might be less physically demanding and focused more on household maintenance. There technology plays a more significant role, with exposure to television, mobile phones, and the internet becoming increasingly common, particularly among middle-class families. However, urban life also presents its own set of challenges; children from informal settlements might face overcrowding, inadequate sanitation, and the everyday struggles associated with urban poverty. Regardless of location, family and community remain central pillars of a Namibian child's upbringing, with extended family networks often playing a crucial role in care and support, embodying the spirit of Ubuntu – "I am because we are."

In stark contrast, children in urban centres like Windhoek or Swakopmund often experience a more modern existence. While chores are still present, they might be less physically demanding and focused more on household maintenance. There technology plays a more significant role, with exposure to television, mobile phones, and the internet becoming increasingly common, particularly among middle-class families. However, urban life also presents its own set of challenges; children from informal settlements might face overcrowding, inadequate sanitation, and the everyday struggles associated with urban poverty. Regardless of location, family and community remain central pillars of a Namibian child's upbringing, with extended family networks often playing a crucial role in care and support, embodying the spirit of Ubuntu – "I am because we are." Education for children in Namibia is both compulsory and free from the ages of 6 to 16yrs, although, as in many other countries, the cost of school upkeep and books etc falls down to the family. Primary school enrollment rates are generally high, often exceeding 90%, reflecting the government's commitment to universal primary education. However, completion rates, particularly at the secondary level, still present a hurdle, with dropouts often linked to financial constraints, early marriage, or the need for children to contribute to household incomes.

Education for children in Namibia is both compulsory and free from the ages of 6 to 16yrs, although, as in many other countries, the cost of school upkeep and books etc falls down to the family. Primary school enrollment rates are generally high, often exceeding 90%, reflecting the government's commitment to universal primary education. However, completion rates, particularly at the secondary level, still present a hurdle, with dropouts often linked to financial constraints, early marriage, or the need for children to contribute to household incomes.

Health disparities continue to threaten child well-being. Malnutrition, stemming from food insecurity and inadequate dietary diversity, undermines physical and cognitive development, making children more susceptible to illness. While the fight against HIV/AIDS has yielded successes, the disease still impacts families, leaving many children orphaned or vulnerable. Access to essential healthcare services for children in Namibia is not uniform across the country, with remote communities often enduring a scarcity of clinics, medical personnel, and essential medicines. Furthermore, issues like childhood tuberculosis and preventable diseases remain a concern in areas with poor sanitation and crowded living conditions.

Health disparities continue to threaten child well-being. Malnutrition, stemming from food insecurity and inadequate dietary diversity, undermines physical and cognitive development, making children more susceptible to illness. While the fight against HIV/AIDS has yielded successes, the disease still impacts families, leaving many children orphaned or vulnerable. Access to essential healthcare services for children in Namibia is not uniform across the country, with remote communities often enduring a scarcity of clinics, medical personnel, and essential medicines. Furthermore, issues like childhood tuberculosis and preventable diseases remain a concern in areas with poor sanitation and crowded living conditions. There are normally about four children in each family (three in urban areas, five in rural areas) living in traditional homes made from sticks and mud. Without electricity, most cooking is undertaken outside on wood fires and while Namibia has significantly improved rural water acces through the construction of dams, rehabilitation of boreholes, and development of pipelines, challenges remain due to climate change, with drought and other vulnerabilities impacting water resources.

There are normally about four children in each family (three in urban areas, five in rural areas) living in traditional homes made from sticks and mud. Without electricity, most cooking is undertaken outside on wood fires and while Namibia has significantly improved rural water acces through the construction of dams, rehabilitation of boreholes, and development of pipelines, challenges remain due to climate change, with drought and other vulnerabilities impacting water resources.