|

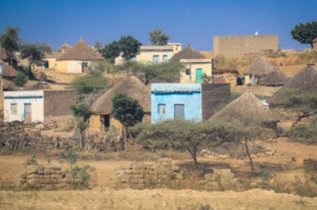

The majority of children in Eritrea (80%) live in rural, often mountainous villages. Due to targeted investments in infrastructure, supportive policies, and broad-based development efforts, Eritrea’s access to clean and safe water has dramatically improved for them over the last few years surging from just 13% in 1991 to around 85% today with groundwater remaining Eritrea’s most reliable source of freshwater. However, rivers, lakes, and aquifers across the country are increasingly under pressure due to overexploitation, deforestation, minimal recharge practices, and the growing impact of climate change. It should be noted that deeply held cultural beliefs hinder many Eritreans from collecting clean water and washing their hands (these beliefs also prohibit the use of latrines during certain hours of the day). The infant mortality rate (under fives) is a currently 39.3 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2025, a significant decrease from previous years, though it remains notably higher than the projected global average of approximately 26.5 deaths per 1,000 live births for the same year. Despite this decline, challenges persist, particularly for newborns and those in rural or conflict-affected regions. The health of Eritrea's children presents a mixed but challenging picture overall. Following its independence, the government made strides in public health, particularly through successful vaccination campaigns that dramatically reduced child mortality from preventable diseases. However, malnutrition, especially stunting (low height for age), remains a serious concern that can have lifelong consequences on a child's physical and cognitive development. While healthcare is officially state-provided, the system is under-resourced, with a shortage of medical supplies, facilities, and trained professionals, especially in remote regions. For many families, reaching a clinic can require a long and difficult journey, making timely medical care an ongoing struggle. Figures for children in Eritrea living in poverty are not available, however that poverty is concentrated in rural areas, affecting the significant portion of a population reliant on rain-fed subsistence agriculture, which is hampered by erratic rainfall and inefficient farming systems. Other factors contributing to this poverty include a history of conflict, limited resources, and poorly implemented poverty alleviation programs. This in a country ranked in 178th place out of 189 countries and territories in terms of life expectancy, literacy, access to knowledge and the living standards of a country in 2025 although, of late, GDP in Eritrea has been growing mainly down to the development of the Bisha mine which is now selling zinc, gold and copper on the international markets. |

Children in Eritrea |

Children in Eritrea |

Children in Eritrea | Children in Eritrea |

|

|

|

The daily routine for many children in Eritrea, particularly in rural areas, is marked by a blend of schooling, chores, and play. The day normally starts before sunrise, with children tasked with helping their families by fetching water from a communal well, tending to livestock, or assisting with farming activities. These responsibilities are not seen merely as work but as an integral part of their contribution to the family’s survival and well-being. This early introduction to responsibility instills a strong work ethic, but it also highlights the economic pressures that shape childhood. Education in Eritrea which is officially compulsory and free, is highly regarded in Eritrean culture and the government has invested in building schools across the country to improve access for all children. However, the path to a complete and quality education is fraught with obstacles. There are three levels of education for children in Eritrea; elementary from 6-11/12yrs, junior from 11/12-15 and high school from 15 -20, however most children go to school either in the morning or afternoon as there are a lack of qualified teachers and actual schools for all children to attend at once. Schooling, which includes mine risk education (a legacy of the 30-year war with Ethiopia), is only compulsory in Eritrea for children from 6 to 14 years and pupils must pass an exam at the end of each school year to be allowed to proceed to the following year. Primary education (grades 1-5) is taught in local language focussing on mathematics, art, social subjects and physical education. Then Basic Secondary education, known as lower/junior or middle level education, lasts 3 years (grades 6-8), and is taught in English. At the end of that three year period, children sit the National Examination and successful candidates can progress onto Senior Secondary education which last for a further four years (grades 9-12). During this latter period, all students learn Maths and English and can select three other subjects from agriculture, biology, book keeping, chemistry, social science, general knowledge, general science, geography, history and physics. At the end of these studies, children in Eritrea sit the Eritrean Secondary Education Certificate Examination (ESECE). Other students who opt not to pursue Senior Secondary education can, from grade 9, attend technical (TVET) programmes which run for 2-3 years and offer courses including automotive engineering, construction, electrical engineering, metalworking, radio technology and woodwork. These courses conclude with the awarding of the TVET-diploma. Enrollment in elementary school is around 81% falling to 59% for lower secondary education. Around 76.6 % of the population are literate (2018 - the last years for available figures), rising to an impressive 93.3 % for children (UNESCO's Institute for Statistics) however, as ever, lower for girls. Perhaps the most defining and challenging aspect of the Eritrean education system is its direct link to the country's policy of indefinite national service. The final year of secondary school, 12th grade, must be completed at the Sawa military and vocational training centre. There, students undergo both academic instruction and rigorous military training. Upon completion, they are conscripted into national service—military, civil, or agricultural— - for an indefinite period. This system profoundly shapes the aspirations and opportunities of young Eritreans. The prospect of a life defined by open-ended conscription, rather than personal choice and career development, looms large over their teenage years, creating a sense of limited horizons and serving as a major driver for the youth who choose to undertake perilous journeys to leave the country in search of other opportunities. Children are often rounded up for national service on the streets and their parents imprisoned if they attempt to escape. One opposition website summarised life for children in Eritrea as having "no educational and career prospects, and the only thing they can look forward to is a lifetime of quiet servitude." Neither are children in Eritrea provided much protection by the law which only makes illegal corporal punishment against children under the age of 15 illegal which seriously endangers their physical and mental health. This means, in practice, that violence against children both and home and school is generally considered acceptable with little or no awareness of its impact on children's development. The video above shows aspects of daily life for children in Eritrea. There are a few charities you can contact to help children there together with child sponsor programs. |

Eritrea has also made significant progress in improving sanitation access, with the Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) initiative leading to a large number of villages achieving open-defecation-free (ODF) status, a goal established by a December 2018 conference. For example, 93% of Eritrean villages were reported to be ODF by January 2025, indicating a substantial shift from a 2015 situation when only 16% of rural children in Eritrea had access to basic sanitation.

Eritrea has also made significant progress in improving sanitation access, with the Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) initiative leading to a large number of villages achieving open-defecation-free (ODF) status, a goal established by a December 2018 conference. For example, 93% of Eritrean villages were reported to be ODF by January 2025, indicating a substantial shift from a 2015 situation when only 16% of rural children in Eritrea had access to basic sanitation.

Classrooms are often overcrowded, and there is a chronic shortage of learning materials and qualified teachers. Economic pressures force many children to drop out of school, either temporarily or permanently, to work and help support their families.

Classrooms are often overcrowded, and there is a chronic shortage of learning materials and qualified teachers. Economic pressures force many children to drop out of school, either temporarily or permanently, to work and help support their families.