|

Cameroon History |

Cameroon History |

Cameroon History | Cameroon History |

For information, videos and photos about the African nation of Cameroon, check out our profile pages.

More >

|

|

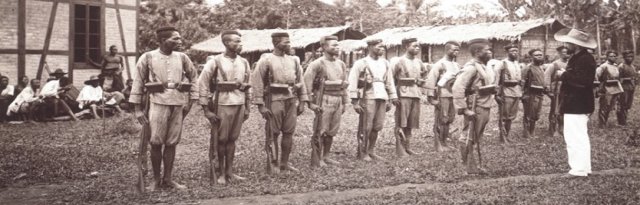

Notable uprisings, though ultimately crushed, included those led by figures like Rudolf Douala Manga Bell, a prominent Duala chief who protested German land policies and was executed in 1914. Despite the harshness of their rule, the Germans left a lasting legacy of modern infrastructure and administrative structures that would influence subsequent colonial powers. The First World War brought an end to German colonial rule in Kamerun. Allied forces, predominantly British and French, invaded the territory, leading to its partition. Following Germany's defeat, the League of Nations formally divided Kamerun into two mandates: French Cameroon (approximately four-fifths of the territory) and British Cameroon (a smaller, contiguous strip along the Nigerian border). After World War II, these mandates were reclassified as United Nations Trusteeships. French Cameroon pursued a policy of direct rule, aiming for the assimilation or association of its African subjects into French culture and administration. French was made the official language, and a centralised administrative system was imposed. This period saw the rise of significant nationalist movements, most notably the Union des Populations du Cameroun (UPC), founded in 1948 by Ruben Um Nyobé, Félix Moumié, and Ernest Ouandié. The UPC advocated for immediate independence and the reunification of the two Cameroons. Their militant stance led to their banning by the French authorities in 1955, followed by a violent anti-colonial rebellion that continued even after independence.

The mid-20th century witnessed the tide of decolonisation sweep across Africa and, on January 1, 1960, French Cameroon gained independence, becoming the Republic of Cameroon, with Ahmadou Ahidjo (above) as its first President. However, the question of British Cameroon's future at that time remained unresolved. In February 1961, a UN-sponsored plebiscite was held in British Cameroon, offering two choices: join independent Nigeria or unify with the independent Republic of Cameroon. The results reflected the regional differences: Northern Cameroons voted to join Nigeria, while Southern Cameroons voted overwhelmingly to unify with the Republic of Cameroon. On October 1, 1961, the Federal Republic of Cameroon was formed, comprising two federated states: East Cameroon (formerly French) and West Cameroon (formerly Southern British). This reunification was a momentous occasion, bringing together disparate colonial legacies under one flag, but it also contained the seeds of future challenges stemming from the integration of distinctly different legal, educational, and administrative systems.

President Ahmadou Ahidjo was re-elected president in 1965, 1970, 1975 and 1980 however he resigned on 4 November 1982 citing health issues. Power transferred to his constitutional successor, Paul Biya (above, left), who had served as his Prime Minister, however they soon fell out and Ahidjo was forced into exile the following year, dying in Senegal in 1989. During this period, Biya effectively wiped his predecessor's rule from history removing his supporters from office and replacing all images of the country's first president with his own. Biya initially embarked on a cautious program of liberalisation, renaming the party the Cameroon People's Democratic Movement (CPDM – Rassemblement démocratique du peuple Camerounais, RDPC) and signalling a shift towards greater democracy. However, a coup attempt in 1984, which Biya narrowly survived, solidified his grip on power and led to further centralisation. The 1990s brought multi-party politics to Cameroon under pressure from both internal dissent and international donors. While multiple parties were legalised, elections often faced accusations of irregularities, leading to ongoing political tensions. Biya remains in office to this day and he maintains a firm grip on power however there has been movement towards democratic reform with the introduction of multi-party politics. He is now the second longest ruling president in Africa and the longest serving non-royal leader in the world. The video explores Cameroon history in more detail. |

British Cameroon was administered as two separate entities: Northern Cameroons and Southern Cameroons, both governed indirectly as parts of the larger British colony of Nigeria. This led to distinct administrative and political developments. Southern Cameroons, with its vibrant political life, developed its own House of Assembly and engaged in debates about its future. Northern Cameroons, predominantly Muslim, was administered alongside Nigeria's Northern Region. The differing colonial policies and administrative integration strategies would sow the seeds for future divisions and the Anglophone problem of today.

British Cameroon was administered as two separate entities: Northern Cameroons and Southern Cameroons, both governed indirectly as parts of the larger British colony of Nigeria. This led to distinct administrative and political developments. Southern Cameroons, with its vibrant political life, developed its own House of Assembly and engaged in debates about its future. Northern Cameroons, predominantly Muslim, was administered alongside Nigeria's Northern Region. The differing colonial policies and administrative integration strategies would sow the seeds for future divisions and the Anglophone problem of today. Ahmadou Ahidjo's reign was characterised by a gradual centralisation of power. Initially hailed as a unifying figure, Ahidjo progressively dismantled the federal structure. In 1972, following a referendum, the Federal Republic was abolished, replaced by a unitary state, the United Republic of Cameroon. This move, while ostensibly aimed at strengthening national unity, effectively diminished the autonomy of the Anglophone West Cameroon, contributing to grievances that would resurface decades later. This loss of autonomy for Southern Cameroons created a strong movement there to break away and form the independent Republic of Ambazonia. Indeed this was proclaimed in 1999 but gained no recognition either within and outside of Cameroon. (In 2016 this Anglophone Crisis erupted again and escalated from peaceful protests into a full-blown armed conflict). In the meantime, Ahidjo fostered a one-party system under the Cameroon National Union (CNU) and pursued a policy of planned economic development, benefiting from the discovery of significant oil reserves in the late 1970s.

Ahmadou Ahidjo's reign was characterised by a gradual centralisation of power. Initially hailed as a unifying figure, Ahidjo progressively dismantled the federal structure. In 1972, following a referendum, the Federal Republic was abolished, replaced by a unitary state, the United Republic of Cameroon. This move, while ostensibly aimed at strengthening national unity, effectively diminished the autonomy of the Anglophone West Cameroon, contributing to grievances that would resurface decades later. This loss of autonomy for Southern Cameroons created a strong movement there to break away and form the independent Republic of Ambazonia. Indeed this was proclaimed in 1999 but gained no recognition either within and outside of Cameroon. (In 2016 this Anglophone Crisis erupted again and escalated from peaceful protests into a full-blown armed conflict). In the meantime, Ahidjo fostered a one-party system under the Cameroon National Union (CNU) and pursued a policy of planned economic development, benefiting from the discovery of significant oil reserves in the late 1970s.