|

Beyond domestic politics, Khartoum is a crucial diplomatic hub. It hosts numerous foreign embassies, consulates, and the regional offices of international organisations, including various United Nations agencies, the African Union, and other non-governmental organisations. This concentration of diplomatic presence underscores Khartoum's strategic importance not just within Sudan, but also within the wider Horn of Africa and Arab world, making it a focal point for regional and international relations.

Prior to the devastating conflict that erupted in April 2023, Khartoum was the undisputed economic engine of Sudan. Its economy was largely driven by the services sector, including government administration, finance, trade, and logistics. The city was home to the headquarters of major banks, financial institutions, and the Sudan Stock Exchange, making it the country's financial core.

While Sudan's industrial base is relatively small, Khartoum hosted a concentration of light industries, including food processing, textiles, pharmaceuticals, and consumer goods manufacturing. Its strategic location meant it served as a major distribution centre for goods imported via Port Sudan and for agricultural products sourced from the fertile Nile basin, particularly the Al-Gezira Scheme. The city's numerous markets, such as the sprawling Souq Omdurman, were vibrant centres of trade, catering to a diverse range of goods and services, from traditional crafts to modern electronics.

The informal sector also played a substantial role, providing livelihoods for a significant portion of the population. However, the recent conflict has inflicted catastrophic damage to Khartoum's economy, leading to widespread destruction of infrastructure, massive displacement of populations, and a near-complete halt of economic activity, posing immense challenges for recovery.

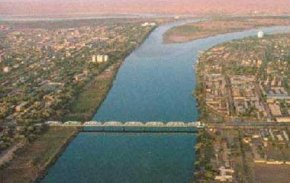

Khartoum is a melting pot of Sudan's diverse ethnic and cultural groups, reflecting the nation's rich tapestry. The city's social fabric is predominantly Muslim, with a strong emphasis on community, family, and hospitality, which are deeply ingrained Sudanese values. While public spaces for cultural expression were traditionally limited, a vibrant intellectual and artistic scene existed, particularly within private gatherings, universities, and cultural centres. Sudanese music, known for its unique rhythms and melodies, often fills the air in homes and local gatherings. If visiting, places of interest to visit include the National Museum of Sudan with exhibits from throughout Sudan's history, Tuti Island at the convergence of the Blue and White Niles from where great views of each can be seen from Tuti's small village with its narrow streets and shops; the natural History Museum and the Mahdi's Tomb which was rebuilt following World War II.

Education is highly valued in Khartoum. The city is home to some of Sudan's oldest and most prestigious universities, including the University of Khartoum, Sudan University of Science and Technology, and Al-Neelain University, attracting students from across the country and the wider region. These institutions have historically been centres of intellectual discourse and social change.

Daily life in Khartoum, prior to the conflict, was characterised by bustling markets, community interactions at local mosques and tea shops, and the regular rhythm of work and social engagement. Sudanese cuisine, known for its hearty stews, grilled meats (mashweya), and a variety of delicious breads, was enjoyed in family homes and local eateries. The Nile itself served as a recreational space, with families often gathering along its banks in the evenings.

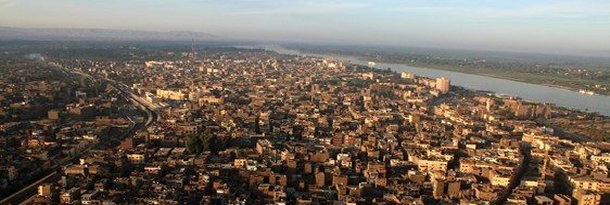

Like many rapidly growing cities in the developing world, Khartoum grappled with significant infrastructure challenges even before the recent conflict. While major bridges and a relatively extensive road network existed, traffic congestion was a persistent issue. Khartoum International Airport served as the country’s main gateway, although plans for a larger, modern international airport outside the city had been repeatedly delayed.

Utilities, including electricity and water supply, often faced strains due to high demand and ageing infrastructure. Housing varied widely, from modern apartment complexes to older colonial-era buildings and expansive informal settlements that grew on the city's outskirts, reflecting the socio-economic disparities within the population. Environmental challenges, such as waste management, air pollution from dust, and the severe heat, added layers of complexity to urban governance. The 2023 conflict has exacerbated all these challenges to an unimaginable degree, leaving much of the city's infrastructure in ruins, displacing millions, and creating an unprecedented humanitarian crisis, turning a once bustling capital into a shadow of its former self.

|

The climate of Khartoum is typical of a hot desert, characterised by scorching summers (reaching well over 40°C) and warm winters. Dust storms (haboobs) are common, particularly during the transitional seasons. The annual rainy season, though brief (July to September), brings some relief and greening to the landscape. This harsh environment has historically underscored the indispensability of the Niles, which not only furnish water for drinking and irrigation but also temper the surrounding aridity, making the area habitable for millions.

The climate of Khartoum is typical of a hot desert, characterised by scorching summers (reaching well over 40°C) and warm winters. Dust storms (haboobs) are common, particularly during the transitional seasons. The annual rainy season, though brief (July to September), brings some relief and greening to the landscape. This harsh environment has historically underscored the indispensability of the Niles, which not only furnish water for drinking and irrigation but also temper the surrounding aridity, making the area habitable for millions.